Vintage Recordings (1964–1966) | Liner notes

Introduction

Wouter Swets (1930–2016) was a well-known and notable Dutch ethnomusicologist, musician, composer, teacher and writer. Through lectures, workshops, radio programs, scholarly articles, polemics, CD reviews, and performances with his orchestras Čalgija and Al-Farabi, Swets inspired countless music lovers and musicians to share his passion for the musical traditions of the Balkans, Anatolia, Arabia and Central Asia, his understanding of which was rooted in the massive collection of beautiful melodies he collected over his life. Even though he would have argued that ‘world music’ does not actually exist as a genre, he has often been called its godfather in the Netherlands. These are the only recordings of Čalgija’s first line-up, originally issued on EP (7″ 33⅓ RPM vinyl). As far as we know, they might be the first Dutch world music recordings altogether, at least in this particular genre.

The album is very charming, a typical product of the 1960s, that is, of young people exploring music they found infinitely more interesting and exciting than the rather dire music that was popular in the Netherlands at that time. But while the emerging Dutch pop scene took its inspiration from the west, Čalgija looked east. The EP is basically a compilation of rehearsal room recordings, taped between 1964 and 1966, with the same recorder Swets used for ethnomusicological fieldwork. At that time, Swets’ band members were still students. In 1967, they left Čalgija in order to be able to focus on their graduation and then have careers, to the great dismay of Swets, who founded a new Čalgija ensemble that existed from 1969 to 1995 and acquired international fame.

Michiel van der Meulen

Bunnik, January 2017

Track notes

Tracks [2], [4], [5] and [6] are basically conscientious interpretations of melodies from mainland Greece, albeit within limitations presented by the instrumentation (accordions are not Greek traditional instruments). Track [1] and [3] are discussed in some detail, because they represent the incipient stages of band leader Wouter Swets’ hallmark approaches in ethnomusicology and as a musician.

[1] Kostursko Oro (Macedonian: Костурско Oро, ‘Dance from Kostur’)

Dance song from what is now Greek Macedonia in a 7/8 meter (SQQ); Kostur (Костур) is the Slavic name for Kastoriá (Greek: Καστοριά). In recordings from the Republic of Macedonia or the predecessor constituent Yugoslavian socialist republic, the melody is often played in a major scale and sung in parallel thirds. Sometimes, the second voice is even used as a solo first, discarding the basic melody. The result is a cheerful sweetness that contrasts somewhat with the lyrics (see below) and would, no doubt, have been eloquently but firmly disapproved by Wouter Swets.

Swets’ arrangement has two elements that were to become typical of his later work. The first is the restoration of a melody to what he considered the, or at least a possible original version, either using the most authentic and/or oldest recordings he could lay his hands on, or by making a reconstruction entirely by himself, guided by scientific principles and his own sense of aesthetics. Here, he discarded the modern use of parallel intervals and (much of) the harmonisation this brings, and used a traditional, more primitive melody + drone polyphony that is still commonly used in the Balkans, and which better suits the modal roots of the music.

The second element is represented by the giriş taksimi (Turkish: introductory ametric improvisation), played by Swets on the accordion in his very distinctive phrasing style (0:04–0:36). The mode of Čalgija’s version of the Kosturkso Oro, with a minor second degree and the fifth being the dominant, is Phrygian. Instead of simply using the same intervallic structure for his improvisation, Swets drew from makam, the Ottoman / Turkish modal system, albeit with the limitations of his tempered instrument that cannot produce the required microtonal intervals. He starts off in makam Kürdî, which is the closest match to phrygian in this modal system, but emphasises the fourth degree. So in order to be able to emphasise the fifth, he modulates back and forth to a tempered approximation of makam Hüseynî (upper register, 0:18). For flavour, he adds a hint of makam Karcığar (a common modulation of Hüseynî; 0:25) and makes his conclusion in makam Nev-Eser (which is actually not very common; 0:30). Later in his career, Swets would systematically assess the modality of Balkan melodies, particularly in terms of the makam system. In order to be able to produce microtonal intervals, he started playing kanun in the 1970s and a specially programmed synthesizer in the 1980s.

Lyrics¹

Додек jе мома при маjка

До ту jе бела и црвена

До ту jе одила, шетала

Момински песни пеjала

Момински песни пеjала

момински ора играла

Годи се, зацрнела се

Ожени се, закопа се

А што се свекор и свекрва?

Това jе црно црнило

А што се девер и золва?

Това jе зхолто зхолтило

А што се малките деца?

Това се ситни синджири

А што jе китка шарена?

Това jе првото либе

__________________

¹ Lines sung in Swets’ arrangement

are underlined.

Transliteration

Dodek je moma pri majka

Do tu je bela i crvena

Do tu je odila, šetala

Mominski pesni pejala

Mominski pesni pejala

mominski ora igrala

Godi se, zacrnela se

Oženi se, zakopa se

A što se svekor i svekrva?

Tova je crno crnilo

A što se dever i zolva?

Tova je zholto zholtilo

A što se malkite deca?

Tova se sitni sindžiri

A što je kitka šarena?

Tova je prvoto libe

Translation

While a girl lives with her mother

Until then she is fair and rosy

Until then she goes walking

Until then she sings girls’ songs

She sings girls’ songs

She dances girls’ dances

She gets engaged, turns black²

Gets married, is buried

And what are father and mother-in-law?

They are black ink³

And what are brother and sister-in-law?

They are yellow dye⁴

And what are the little children?

They are little chains

And what is the colorful bouquet?

It is her first love

__________________

² black = unhappy.

³ black ink = unhappiness.

⁴ yellow dye = sickness.

Čalgija performing amidst dancers in Amsterdam. Musicians (L-R): Pedro van Meurs (tapan), Wouter Swets (accordion), Terry Agerkop (guitar) and an unidentified gajda player. Photo: Henk Arends (1962/63); © Pan Records.

[2] Maniátikos (Greek: Μανιάτικος)

Well-known dance melody from Mani, the central peninsula of three protruding from the Southern Peloponnese into the Mediterranean sea. The meter is 7/8 (SQQ, kalamatianós).

[3] And΄ áman palikári (Greek: Αντ΄άμαν παλικάρι, ‘When I was a boy’)

Song to a tap’nos (ταπ’νός or ταπεινός) dance from Western Thrace, i.e., the Greek part of a region shared with Bulgaria and Turkey (Northern and Eastern Thrace, respectively). The meter is 4/4. It is typically sung by the dancers accompanied by drums, and if melody instruments are used, they will traditionally be gaida (bagpipes) or lyra (fiddle). In either case there is no harmonisation except for a drone. Swets’ arrangement of the dance reveals that, even though he was very much interested in the modal roots of Balkan music, he liked to indulge in harmonisation too: he was, after all, trained as an organ player. This might explain why he couldn’t resist using the Emin7 chords heard in the first two bars and throughout. The chord progressions starting at 0:38 seems to be inspired by Northern Thracian music, which can be, like a lot of Bulgarian music, lushly harmonised. He would later explore the harmonisation of modal music in more depth, with unexpected, sophisticated and very characteristic results.

Lyrics⁵

Αντά ’μαν⁶ παλικάρι δώδεκα χρονώ,

αντά ’μαν παλικάρι δώδεκα χρονώ,

στα σίδερα πατούσα κι έβγαζα νερό,

στα μάρμαρα πατούσα και κουρνιάχτιζαν.

Γιανίτσαρο μι πήραν πέρα στη Φραγκιά, γιανίτσαρο μι πήραν πέρα στη Φραγκιά,

να μάθω το δοξάρι και τον πόλεμο,

να μάθω το δοξάρι και τον πόλεμο.

Kι ούδε δοξάρι ’μάθα κι ούδε πόλεμο,

κι ούδε δοξάρι ’μάθα κι ούδε πόλεμο.

Μόν’ ’μαθα την αγάπη την παντέρημη,

μόν’ ’μαθα την αγάπη την παντέρημη.

__________________

⁵ NB: Čalgija’s rendition is instrumental.

⁶ Erroneous spelling on the original EP label corrected.

Transliteration

Antá ’man palikári dódeka chronó,

antá ’man palikári dódeka chronó,

sta sídera patoúsa ki évgaza neró,

sta mármara patoúsa kai kourniáchtizan.

Gianítsaro mi píran péra sti Frankiá,

gianítsaro mi píran péra sti Frankiá,

na mátho to doxári kai ton pólemo,

na mátho to doxári kai ton pólemo.

Ki oúde doxári ’mátha ki oúde pólemo,

ki oúde doxári ’mátha ki oúde pólemo.

Món’ ’matha tin agápi tin pantérimi,

món’ ’matha tin agápi tin pantérimi.

Translation

When I was a twelve-year-old boy,

when I was a twelve-year-old boy,

I walked on iron squeezing out water⁷,

I walked on stone reducing it to dust.

As a janissary⁸ I was sent far afield,

as a janissary I was sent far afield,

to learn about archery and warfare,

to learn about archery and warfare.

I didn’t learn about archery and warfare,

I didn’t learn about archery and warfare,

I only learned about eternal love,

I only learned about eternal love.

__________________

⁷ Metaphor to describe his good health and physical strength.

⁸ Member of the Ottoman Sultan’s personal elite infantry corps, who were recruited at a young age.

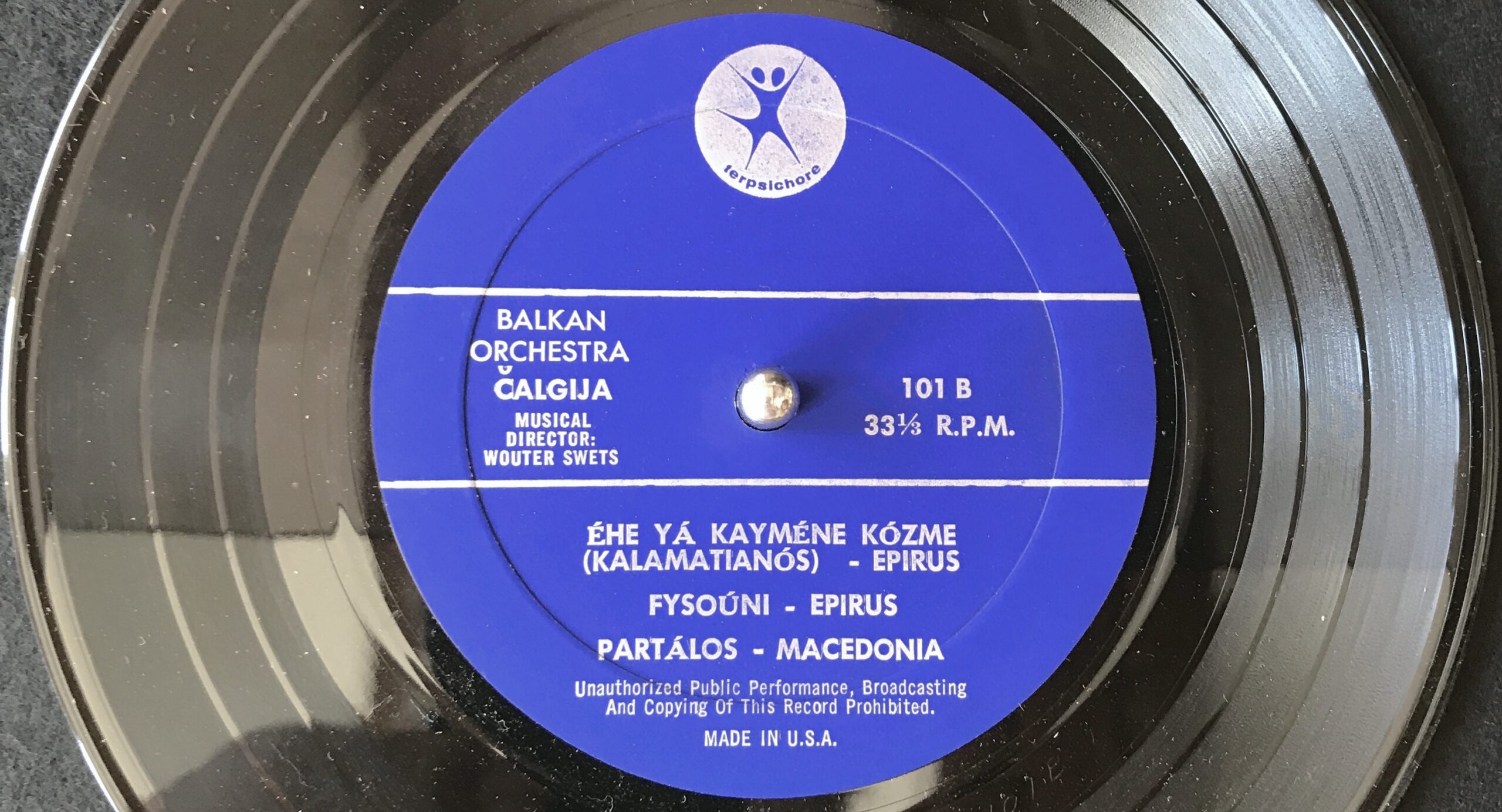

[4] Éhe yá kayméne kózme (Greek: Έχε γειά καημένε κόσμε, ‘Farewell poor world’)

Kalamatianós (7/8) dance from Epirus, a.k.a. Chorós tou Zalóngou (Χορός του Ζαλόγγου, ‘Dance of the Zalongos’). The title refers to a song that was reportedly sung by sixty three women from the town of Souli while dancing and throwing their children and then themselves into the gorge of mountain Zalongos in 1803, dying rather than falling into the hands of the Ottoman troups that had just overrun their semi-autonomous home region.

Lyrics⁹

Έχε γεια καημένε κόσμε,

έχε γεια γλυκιά ζωή,

και ’συ δύστυχη πατρίδα,

έχε γεια παντοτινή.

Έχετε γεια βρυσούλες,

λόγγοι, βουνά, ραχούλες.

Έχετε γεια βρυσούλες,

και σεις Σουλιωτοπούλες.

Στη στεριά δε ζει το ψάρι,

ούτ’ ανθός στην αμμουδιά,

κι οι Σουλιώτισσες δεν ζούνε,

δίχως την ελευθεριά.

Έχετε γεια βρυσούλες, …

Οι Σουλιώτισσες δε μάθαν,

για να ζούνε μοναχά,

ξέρουνε και να πεθαίνουν,

να μη στέργουν στη σκλαβιά.

Έχετε γεια βρυσούλες, …

__________________

⁹ NB: Čalgija’s rendition is instrumental.

Transliteration

Éche yia kaiméne kósme,

éche yia glikiá zí,

kai ’si dístichi patrída,

éche yia pantotiní.

Échete yia vrisoúles,

lóngi, vouná, rachoúles.

Échete yia vrisoúles,

kai sis Souliotopoúles.

Sti steriá de zi to psári,

oút’ anthós stin ammoudiá,

ki i Souliótisses den zoúne,

díchos tin eleftheriá.

Échete yia vrisoúles, …

I Souliótisses de máthan,

yia na zoúne monachá.

Xéroune kai na pethaínoun,

na mi stérgoun sti sklaviá.

Échete yia vrisoúles, …

Translation

Farewell poor world,

farewell sweet life,

and you, poor fatherland,

farewell forever.

Farewell springs,

valleys, mountains, hills.

Farewell springs,

and you women of Souli.

Fish cannot live on land,

nor a flower on the sand,

and the women of Souli cannot live,

without their freedom

Farewell springs, …

The women of Souli did not only learn,

how to survive on their own.

They also know how to die,

to not succumb to slavery.

Farewell springs, …

[5] Fysoúni (Greek: Φυσούνι, ‘Bellows’)

Well-known dance from Epirus in 9/8 (QQQS, karsilamás). In comparison with most Epirotic dances, Fysoúni is fast and upbeat.

[6] Partálos (Greek: Παρτάλος)

Macedonian men’s dance from the area of Thessaloniki in 6/4, having a six-step pattern of leaps and squats.

Čalgija performing amidst dancers in Amsterdam. Musicians (L-R): Pedro van Meurs (tapan), Albert van der Meulen (accordion) and Wouter Swets (accordion). Photo: Henk Arends (1962/63); © Pan Records.

Other releases by Čalgija

- Üçayak / TouMilou #5, 2021 / album

- Unforgotten / PAN 2056 / TouMilou #4, 2020 / album

- Mosaique Vivant / MV695, 1995 / compilation album with three tracks by Čalgija

- Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2 / PAN 2007CD, 1991 / album

- Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #1 / MU 7425, 1978 / PAN 7425, 2013 / album