Ücayak | Liner notes

Introduction

About this album

Čalgija was a Dutch ensemble that existed from 1969 till 1995, led by the late Wouter Swets (1930–2016), who aimed to perform ethnomusicologically sound arrangements of traditional music from the Balkans and Anatolia. The underlying assumption was that this music had suffered from westernisation since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, and in his arrangements Swets set out to restore pieces into more pristine states. This might suggest that Čalgija’s music was cerebral and contrived, but it is quite the opposite: their instantly recognisable arrangements, instrumentations and overall sound were vibrant and original.

Čalgija released two albums during its long existence. Their debut LP Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #1 (Munich MU7425, 1978) was very successful and is still considered one of the best Dutch productions of its kind. They released a long-awaited second album Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2 in 1991 (Pan 2007CD). When it came to live performances and popularity however, Čalgija had its heyday in the late 1970s and early to mid 1980s, and many wondered why the ensemble did not release another album during that period.

We know that they tried. Their 1991 album featured recordings made in 1983/84, but the liner notes do not explain why these tracks were not released at that time. It is a less known fact that Čalgija recorded an album in 1981 that was mixed and mastered but never released, reportedly because Swets was unable to finish the liner notes. When I first heard this, my curiosity was aroused. I set out to search for the master tapes, only to find out that they had been kept by the record company (Munich Records and its successors) for tens of years, but were discarded sometime around 2010. However, the search did result in finding the master tape of the aforementioned 1983/84 recordings, which included several unreleased tracks. I realised that the aim had been to make an album, but the recordings were shelved—again—to be partially reused on the later CD. We decided to release that material in its original form, supplemented with live recordings, on an album entitled Unforgotten – Music from the Balkans and Anatolia (Pan 2056, 2020). I refer you to the liner notes of that album for more information about that particular discovery and the general history of Čalgija.

Čalgija around 1978. Front row (LR): Remco Busink (who left the group in 1978), Wouter Swets, Thijs de Melker, Jan Hofmeijer; back row (LR): Roel Sluis, Tjarko ten Have, Crispijn Oomes, Roelof Rosendal. Photo: Remco Busink.

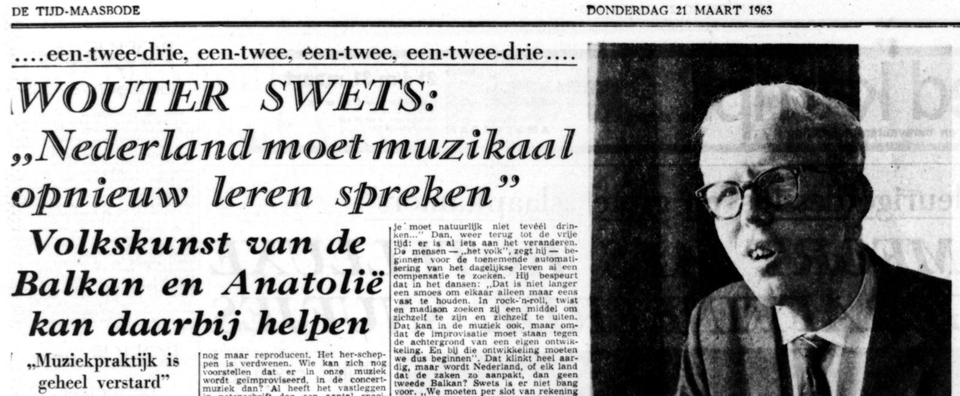

Čalgija’s mystery album unearthed

After the release of Unforgotten, a cassette copy of the 1981 master tapes was found in the estate of Wouter Swets. It was marked “cd Čalgija I restopn.” (CD Čalgija residual rec.) in Swets’ unmistakable handwriting, which suggests that he had at some point abandoned the idea of releasing the material as an album, but was considering reusing at least some of it on a CD. A former manager of Munich Records, whom I contacted in my earlier search for the album, had in fact told me that during his many attempts to convince Swets to finalise the production, he also suggested to make a CD—a novelty at the time—instead of the originally envisaged LP. In the end, the matter was settled, the project was abandoned and Čalgija, which had meanwhile changed its line-up, made a new attempt from scratch.

The cassette copy of the master tape of Čalgija’s 1981 recordings, which turned up in the estate of Wouter Swets. Photo: Michiel van der Meulen.

I was present when the music sounded in the very studio where it was recorded, mixed and mastered 40 years before, played by the very same engineer on the very same equipment. Most of the material turned out to be good in terms of performance and sound quality, and some of it represents Čalgija at its best. Three tracks were redone in later sessions, for example the Balkan-Turkish song ‘Köşküm var’, which was recorded again in 1983/84 (released on Unforgotten), and then again in 1990 (released on Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2). I think I understand why Swets had become dissatisfied with his first attempt. While he was struggling with the liner notes, he was also working on Traditionele Turkse Kunstmuziek, a textbook in Dutch on Turkish art music. His studies must have made him realise that a particular modulation in his arrangement of the song, which included a chromatic motion, was awkward from a modal point of view. The modulation was removed in the much better 1983/84 version, and the 1990 version differed only in tempo and instrumentation. I would consider it disrespectful to Swets to release posthumously a track he had discarded for artistic reasons, and we have therefore excluded it from this album.

The recordings also included versions of the Turkish song ‘Acem kızı’ and the Bulgarian dance melody ‘Tronkata’, which were both redone in 1983/84 and are included on Unforgotten. In terms of performance and arrangement the earlier version of ‘Acem kızı’ is fine, but of somewhat lesser quality than the later recording, so we decided that including it would bring no added value to Čalgija’s published repertoire. The 1981 version of ‘Tronkata’ is so similar to that of 1983/84 that there must have been non-musical reasons to redo it – most probably the new line-up. In any case, we decided to leave this track out as well. That left us with nine tracks, which needed to be put in a different order to work well, and supplemented with additional material. We reverted to concert recordings of 1978 from the archives of Pan Records, which feature mostly the same line-up.

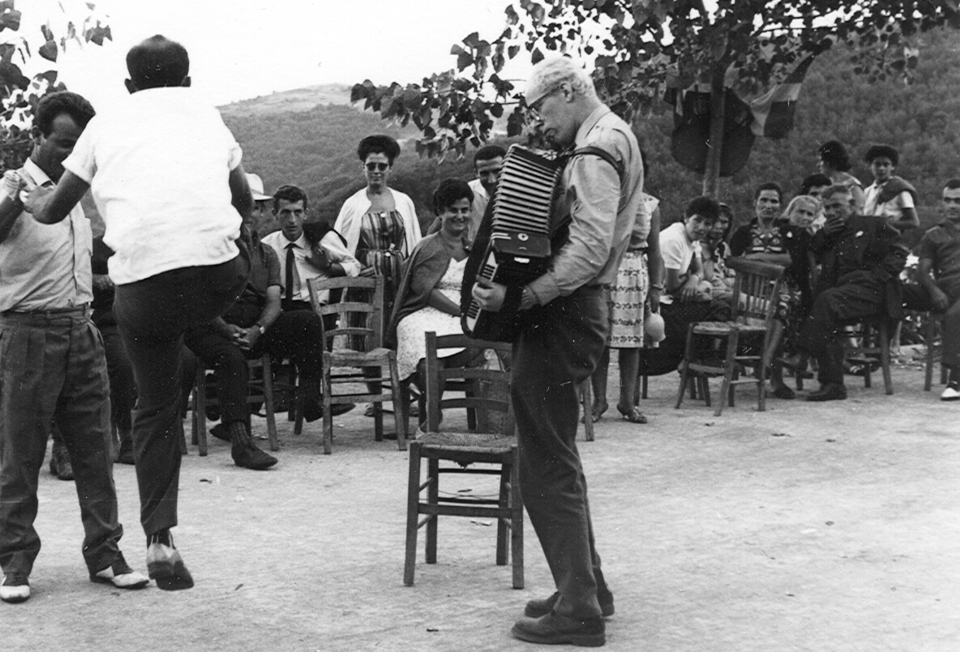

Laying the groundwork: Wouter Swets playing his accordion while on ethnomusicological fieldwork in Greece. Photo: Henk Arends, 1965; © Pan Records.

Reconciliation

In the liner notes of Unforgotten I speculated that dissatisfaction was the reason for Wouter Swets to shelve two consecutive album projects in the 1980s. Retrospectively, Swets used that era to complete a transition from the Balkan folk musician he was in the 1960s to the modal musician he would become in the 1990s. Čalgija member Roel Sluis remembers visiting Swets in the Hague, who had just listened to a new Greek record that included an ametric song with intermittent taximia (instrumental improvisations). It made use of makam, the Ottoman/Turkish modal system, but not as hermetically as they experienced Turkish art music at that time. Swets was very enthusiastic: “Roel, this is the future of Čalgija, we should do this too!”

The present album marks the first steps in that direction, and is interesting for that reason alone. The two versions of the Northern Albanian song ‘Në Shkodër’ are a perfect illustration of this. The live version of 1978 [16] is cheerful, and modern in terms of its (lush) harmonisation and the second voice. In 1981, Čalgija recorded the song in a completely different, more austere way [8]. Swets plays the first voice and a drone on his accordion, and they use a Turkish bağlama saz and a Greek laouto to imitate the Albanian çifteli and sharkia lutes played in the authentic modal style of the region.

Altogether, the recordings must have presented Swets with a tough dilemma. The Balkan folk music he was gradually distancing himself from was played well, but I suspect that the quality of the Turkish material he aspired to perform did not meet his rapidly evolving standards. However, by discarding the whole project, Swets deprived his audience from an album that I am sure they would have appreciated.

I remember playing music with, amongst others, my father at a party in the mid-1990s, at which Swets was present as well. He asked my father whether he could play his accordion (…he actually demanded it), and this would become the only time that I performed with Swets myself. He then basically took over the stage, playing an extended suite of east Anatolian folkdance melodies while enjoying himself thoroughly. Afterwards, he said two things that stuck with me. One was a remark following a compliment on an improvisation I made on the violin, “You use a lot of Nikrîz, don’t you?” At that time—I was around 25 years old—I had no idea what he meant, and I am still a bit unsure whether this was supposed to be good or bad. More importantly he mentioned how much he had enjoyed playing folk music, and that it had made him realise how cerebral he had become with Al Farabi, Čalgija’s successor ensemble. I think that this memory of Swets’ nostalgia justifies releasing material from Čalgija’s 1981 recordings. Rather than the beginning of Swets’ modal era, I’d say they mark the end—or the climax, if you like—of the style Čalgija developed in the 1970s, and therefore supplement their acclaimed debut.

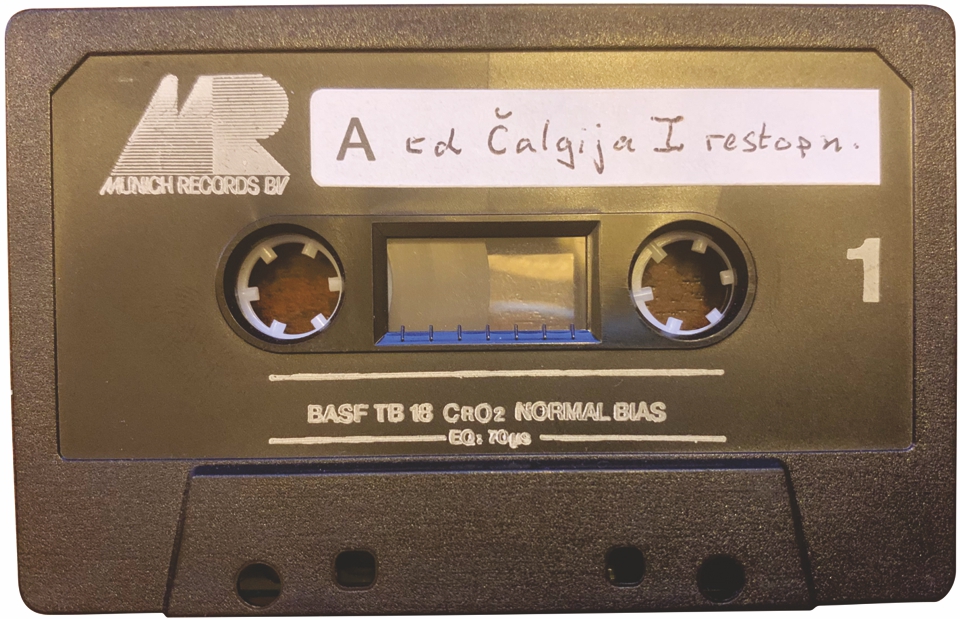

Headline of a read-worthy extended interview with the then 32-year-old musicology student Wouter Swets in the De Tijd-Maasbode (21 March 1963), about his mission to revitalise the Dutch music scene with an infusion of folk music from the Balkans and Anatolia. Translation: Wouter Swets: “The Netherlands should rediscover its musical voice.” / Folk art from the Balkans and Anatolia may be helpful / “Musical practice is completely ossified”

Čalgija at the turn of the 1980s

The studio material on this album was recorded by Wil Hesen, who was in his early twenties at the time and had never heard anything like the music Čalgija was playing. The group made quite an impression on him, particularly their musical director, “He [Swets] kept a tight discipline. He wouldn’t count off a piece; he’d just make a big nod and go, always somewhat unexpectedly while everybody watched him closely. He would get angry if the entrance was imperfect.” Hesen’s imitation of Swets’ characteristic nod immediately evoked memories.

Swets was indeed by all accounts a formidable figure. When I asked his fellow musicians Roel Sluis, Crispijn Oomes and Thijs de Melker about their recollections of Čalgija around the time of these recordings, all three mentioned a study trip the group made to the Balkans in 1980. Oomes recalls Swets making his appearance at Schiphol Airport wearing some sort of tropical uniform, an anachronism bearing testimony to his family roots in the Dutch East Indies, but which most of all shows that he considered the trip a proper expedition. Swets had been doing fieldwork in the region since his ethnomusicology studies in the 1950s. From accounts in the media (he frequently appeared on the radio and gave several newspaper interviews) these journeys had been formative experiences that he now wanted to share with his group.

Čalgija flew to Ohrid, where a worn rental minibus awaited them, and they embarked on a two-week road trip through the Yugoslavian Socialist Republic of Macedonia and Northern Greece. Čalgija’s members soon realised that their trip was not going to be a normal one; when one of them asked where they were going to spend the first night, Swets’ reply was, “This is the Balkans, guys, we’ll just see.”

Thijs de Melker was driving towards their first destination Kruševo when the headlamps failed and high-beam signalling was the only lighting option he was left with. As the sun was setting, De Melker, who had only just obtained his driver’s license, suggested stopping to find help. An argument arose, Wouter Swets’ position being that technicalities and road safety considerations were not to interfere with the far more important business of reaching their destination and playing music: “just drive in the dark, as my father would have!” They drove on as night fell, De Melker using one hand to steer and change gear and the other to operate the headlight lever, switching between invisibility and blinding oncoming traffic. In this way, they reached the small village of Žurče, where De Melker refused to continue because they knew about the bad condition of the curvy mountain road ahead.

Čalgija’s minibus, a Yugoslavian IMV Kombi, in the mountains of Epirus, NW Greece. Photo: Crispijn Oomes, 1980.

Crispijn Oomes’ travelling diary reveals that Čalgija’s first encounter with rural Macedonia, birthplace of music they loved and played, was somewhat anticlimactic. They were in need of a mechanic but there was no garage, they were hungry but there was no tavern, and they were tired but there was no hotel. In fact, the only public place they saw was a barn that appeared to serve as some sort of community hall. Inside, the seven strangers were initially ignored, but the ice broke when Swets decided they would play some music. Čalgija gradually built an audience from passers-by, out on their evening stroll. The villagers recognised the music, were intrigued by the way it was played, sang along, danced to it, and eventually wanted to try Čalgija’s instruments. The cultural contact they established did not solve their more mundane lodging problems however, and the ensemble eventually spread out to find somewhere to sleep. Jan Hofmeijer, Crispijn Oomes and Roel Sluis ended up in a haystack, Thijs de Melker used the car, but Wouter Swets, Tjarko ten Have and Roelof Rosendal were approached by a farmer who was offended that they had passed his house without introducing themselves, denying him the opportunity to offer his hospitality. They were invited in, drank rakija till late and slept comfortably.

The next morning, everybody assembled at the minibus except for Swets, whom Rosendal said was still talking with their host. They joined him at the farm, where food and drinks were served and more music had to be played. In a brief farewell speech, the farmer reproached Swets for having his group sleep rough and himself for being a bad host, and then allowed Čalgija to leave for Kruševo. In the car, Swets spoke highly of his host, who had been a WWII partisan and appeared to be a respected member of the village community. The group teased him: “but, Wouter, we thought you didn’t like communists?” to which the politically conservative Swets replied, “No, but this was a good one.”

After a couple of days, Čalgija reached the village of Akritas in Northern Greece, and Swets decided to play music in the local tavern: “guys, get your instruments.” The Macedonian music they played was appreciated by the audience, especially by the youngsters who wanted to buy cassettes that Čalgija hadn’t brought with them. However, after a while a policeman appeared on the scene who summoned Čalgija to stop playing and escorted them back to their hotel in Florina. Akritas, formerly known by its Macedonian name Buf (Буф), is located in one of the hotspot regions of the predominantly Slavic Ilinden revolt of 1903 against the Ottomans. In fact, the uprising had just been commemorated in the Kruševo region, where Čalgija had stayed just days before. Balkan music, which had evidently once been shared across peoples of the vast Ottoman Empire, had inevitably become a matter of dispute when these very same peoples started creating distinctive cultural identities for themselves and their post-Ottoman states. The way Čalgija played, in particular the instrumentation and arrangements, exposed an uneasy past (see the notes to ‘Ti kles, kaimeni Maria’ [7]).

The liner notes of the album Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2 and Swets’ book on Turkish art music tell us, in rather strong words, that Wouter Swets had no patience with what he considered politically motivated revisionism. He simply told people what the music told him. To Swets, the musicological evidence was clear and irrefutable.

Dutch audiences of the time will have enjoyed the anecdotes of Čalgija’s study trip in more or less the same way as Čalgija’s music, which came across to them as exotic, wild, typically Balkan if you like. As the live recordings will tell you, Čalgija’s performances had a level of energy befitting a rock concert, which introduced a weird but charming contrast with the schoolmasterly way Swets would introduce the pieces. However, there was more to it. Swets did not drink with the partisan farmer to act out some romantic image of Balkan life – he could have enjoyed that with any farmer, anywhere. What set the Balkan farmer apart to him was the musical tradition he represented. From the way he studied and treated the material, it seems that everything Swets loved about the Balkans was encapsulated in the music itself. Driving conditions, rakija, barns, partisans, rough nights and policemen were ephemeral.

Wouter Swets (accordion) and Roelof Rosendal (darabuka) playing on the village square of Laista (Epirus, NW Greece). The violin player is local. Photo: Crispijn Oomes, 1980.

Ücayak

This album is named after its third track. The Turkish word üçayak means tripod or, especially in the context of dance, three-step. It is also the name of the ruins of a Byzantine church in the Kırşehir province of Central Anatolia. The full name, Üçayak Kilisesi (Three-legged Church), refers to the state of the ruins, of which the main remaining wall, which features two arched openings, resembles three legs.

The church was reportedly built in the tenth or eleventh century, in an isolated location with no nearby resources of water or signs of habitation. Just like the music Čalgija played, the presence of Orthodox-Christianity in the Anatolian heartland can only be understood from a historical perspective. Just like the archaeologists of the local Ahi Evran University, who want to restore and conserve the church, Swets recognises forgone glory in current renditions of music left behind or taken along by people moving to the modern, monoethnic states that replaced the ethnic-cultural mix of the Ottoman Empire.

The Ücayak church in 1900. Its arches would collapse in 1938 due to an earthquake. Source: Strzygowski, J., Winter Crowfoot, J., Smirnov, J.I. (1903) – Kleinasien, ein Neuland der Kunstgeschichte. Leipzig, Germany: J.C. Hinrichs, 245 pp.

Completion

This album completes an effort to safeguard Čalgija’s musical legacy, which started out of curiosity and resulted in a reissued 1960s EP (2017) and two new full albums, Unforgotten (2020) and the present one, Üçayak. All of their unpublished studio recordings have now been (un)covered, most of the material has been published, along with the best of the concert recordings we have so far identified and digitized.

Following these recordings our focus now turns to Wouter Swets’ written legacy, and this release will be followed by the aforementioned second, annotated edition of Swets’ textbook on Turkish art music, which is currently in the final proofreading stages and will be published in 2023. Future plans include a sheet music book that covers everything recorded on the albums of Čalgija and Al Farabi, and other key examples of Swets’ arrangements of traditional material. Other than that, there is an intriguing, unfinished scholarly manuscript in which Swets described his reconstruction of ‘Dağıtma ey Sabâ’ a kar-ı natik in makam Sabâ by the Ottoman composer Zekâi Dede (1825–1879).

Meanwhile, we will keep an eye out for additional live recordings for the purpose of archiving, but do not expect to release another Čalgija album. According to the ensemble’s former members, their best and most relevant repertoire has now been covered; but then again, who knows what might turn up?

Üçayak has been produced in extraordinary times. While the waning coronavirus pandemic kept me locked down in my home and country, it allowed my mind to travel to the Balkans as I came to know it in my youth, as well as to the hidden pasts and parallel universes that are encapsulated in Čalgija’s music. One can talk about music as much as one likes, one can analyse, interpret, theorise, contextualise, opinionise, but in the end it is only the experience that really matters. You need to listen and let the music do the talking. I hope that you will enjoy this album as much as I did when I first heard its recordings after forty years of silence.

Michiel van der Meulen

Bunnik, Netherlands

April 2021

Čalgija’s instruments (LR). Against wall: oud, violin, clarinet, Bulgarian kaval, PVC kaval, Turkish kanun. On the table: bağlama saz, cura saz, gădulka. In front of table: def, darabuka, Persian santur; tapan to the right. In the front: three gajdas (two Bulgarian, one Macedonian). Not shown: accordion, divan saz, laouto, Macedonian tambura, ney, sopranino recorder. Photo: Eelco Brinkman, source: Čalgija (1978) – Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #1. Wageningen, Netherlands: Münich Records, MU 7425, 1LP.

Track notes

Musicians are indicated with their initials; the photo above features many of the instruments they play:

- WS – Wouter Swets: accordion, kanun

- TH – Tjarko ten Have: gajda, bağlama saz, ney, def, tapan

- JH – Jan Hofmeijer: clarinet, santur, vocals

- TM – Thijs de Melker: Macedonian tambura, laouto, divan saz, oud

- CO – Crispijn Oomes: violin, gădulka, cura saz

- RR – Roelof Rosendal: darabuka, oud, tapan, def, gajda

- RS – Roel Sluis vocals, kaval, sopranino recorder, davul

All material is traditional, and has been analysed and arranged by Wouter Swets. In accordance with Swets’ musicological approaches, modes of Balkan melodies have been interpreted according to the Ottoman/Turkish makam system as much as possible. Irregular compound meters are subdivided in groups of two and three beats, and names given refer either to the dance at hand, or the Ottoman/Turkish usul (rhythmic cycle).

While retaining responsibility for any error, we thank the following people for providing or helping with the lyrics’ translations: Cengiz Arslanpay, Hugo Strötbaum and Yaşar Saka (Turkish, Ottoman-Turkish), Nikos Kokolakis and Vassilis Philippou (Greek), Albana Shala and an anonymous contract translator (Albanian), and Atko Adrović (Macedonian).

[1] Nji ditë diele

Instrumentation: vocals (RS), clarinet (JH), violin (CO), sopranino recorder (RS), accordion (WS), laouto (TM), oud (RR), def (TH). Modes: folkloristic, tempered forms of makams Hüseynî and Gerdâniye. Meter: 9/8 (2 + 2 + 2 + 3).

With this romantic song from Northern Albania, Wouter Swets demonstrated his ability to find gems in the vast Balkan folk repertoire. Because of that country’s isolationist policies during the communist era (1946–1991), it was actually quite difficult for Swets to build an Albanian repertoire. He would transcribe melodies directly from the low-fi MW radio broadcasts of Radio Tirana, results of which still go by names such as ‘Albanese Radio Tirana 1’, or ‘Albanese Sentimental 2’.

Lyrics

Nji ditë t’diele asi zamanit

mblodha shok’t me ba nji heng

Rrijnë dy vajza n’maje t’manit

e s’më lan me nxanun vënd

Mori drandofillja n’gotë

hiqe pak moj at’ shami

Bishtalecin si pavodë

të shof pak moj bukuri

Xhamadanin rrush bajama

peshqesh ty moj ty du me t’a çu

Ishalla tash t’bjen taman

po të tham moj mollë e ftu

Porsi zog tuj fluturu

ulu poshtë e buk’ra vashë

Po të them pra se të du’

n’zemër m’hyne sa të pashë

Translation

Once upon a time on Sunday

I gathered my friends to make a feast

Two girls sat on a mulberry branch

and l couldn’t keep myself in place

You beautiful rose in a glass

remove the scarf from your hair

Your braid like a peacock

show yourself my little beauty

[a] Vest [with embroidered] grapes [and] almonds

I want to bring you as a gift

Befitting if God wishes, I am telling you

my apple and quince

Flying around like a bird

sit down beautiful girl

So I can tell you I love you

you caught my heart at first sight

[2] Trakijsko pajduško | Тракийско пайдушко

Instrumentation: gajda (TH), kaval (RS), gădulka (CO), accordion (WS), tambura (TM, 2×), darabuka (RR). Modes: Phrygian, Ionian and Aeolian. Meter: 5/16 (2 + 3), pajduško.

Quintessential Čalgija-interpretation of a folk dance from Northern Thrace (Bulgaria), which may come across as traditional to lay audiences but is in fact quite unorthodox. In a traditional rendition, a Bulgarian tambura would have been used to play added-tone chords in the characteristic, advanced Bulgarian harmonisation style. Instead, Čalgija used two double-coursed Macedonian tamburas that produce dyads. This introduces a combination of harmonic freedom and ambiguity that brings out the modal character of the melody, and works well with the hypnotic drone of the gajda bagpipe. The tambura arrangement, by the way, is anything but traditionally Macedonian; one basically plays a counterpoint melody that faintly echoes Swets’ training as a classical organ player.

While the studio material on this album was recorded live, some additional tracks were dubbed. For Čalgija this was a first, to which Wouter Swets had agreed with some reluctance. He saw the advantages offered by studio technology, but it went against the sense of tradition that came with playing folk music and his approach in general. In this case, Thijs de Melker played the extra tambura track, maybe to recreate the sound Čalgija had before lute player Remco Busink left.

Altogether, this track is an excellent example of Wouter Swets’ approach as an ethnomusicologist and arranger, which involves recombining elements from distinctive yet related musical traditions, to which he added a personal touch. Interestingly, Čalgija was considered a stronghold of folk purism by their Dutch fans—until Swets started using a microtonal synthesizer in the late 1980s, that is—while in its regions of origin their music was perceived as ‘different’.

[3] Üçayak

Instrumentation: clarinet (JH), sopranino recorder (RS), kanun (WS), bağlama saz (TH), divan saz (TM), oud (RR), darabuka (RR). Mode: makam Karcığar. Meter: 8/16 (1 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2), düyek.

Dance melody from Eastern Anatolia. Turkish folk tunes gave Čalgija its first experience with modal systems and microtonality. Crispijn Oomes still remembers the first time he was requested to play non-Western intervals on his violin, which to him felt like throwing away many years of training to play in tune.

[4] Aman doktor

Instrumentation: vocals (RS), violin (CO), ney (TH), kaval (RS), santur (JH), kanun (WS), oud (TM), darabuka (RR). Mode: makam Sabâ. Meter: 8/8 (1 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2), düyek (çiftetelli).

Well-known folk song originally from Rumelia (the European parts of the Ottoman Empire), also known as ‘Mendilimin yeşili’. Many such songs found their way to Turkey as a result of the Muhacir, i.e., the migration of Ottoman Muslims after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. There is a mixed Turkish-Greek version of the lyrics, which features in an emerging musical dialogue between Turks and Greeks, a hopeful example of culture transcending divisive politics.

Lyrics

Mendilimin yeşili aman aman

ben kaybettim eşimi

Al bu mendil sende sende dursun,

sil gözünün yaşını

Aman doktor canım kuzum doctor

derdime bir çare

Çaresiz dertlere düştüm

doktor bana bir çare

Mendilim benek benek

ortası çarkıfelek

Yazı beraber geçirdik

Kışın ayırdı felek

Aman doktor canım kuzum doctor

derdime bir çare

Çaresiz dertlere düştüm

doktor bana bir çare

Translation

My handkerchief is green

I lost my wife

Take this handkerchief

keep it on you, wipe your tears

Oh, doctor, my dear doctor

a cure for my sorrow

I fell into despair

doctor, cure my sorrow

My handkerchief is mottled

heart of the passion flower

We spent the summer together

we spent the winter apart

Oh, doctor, my dear doctor

a cure for my sorrow

I fell into despair

doctor, cure my sorrow

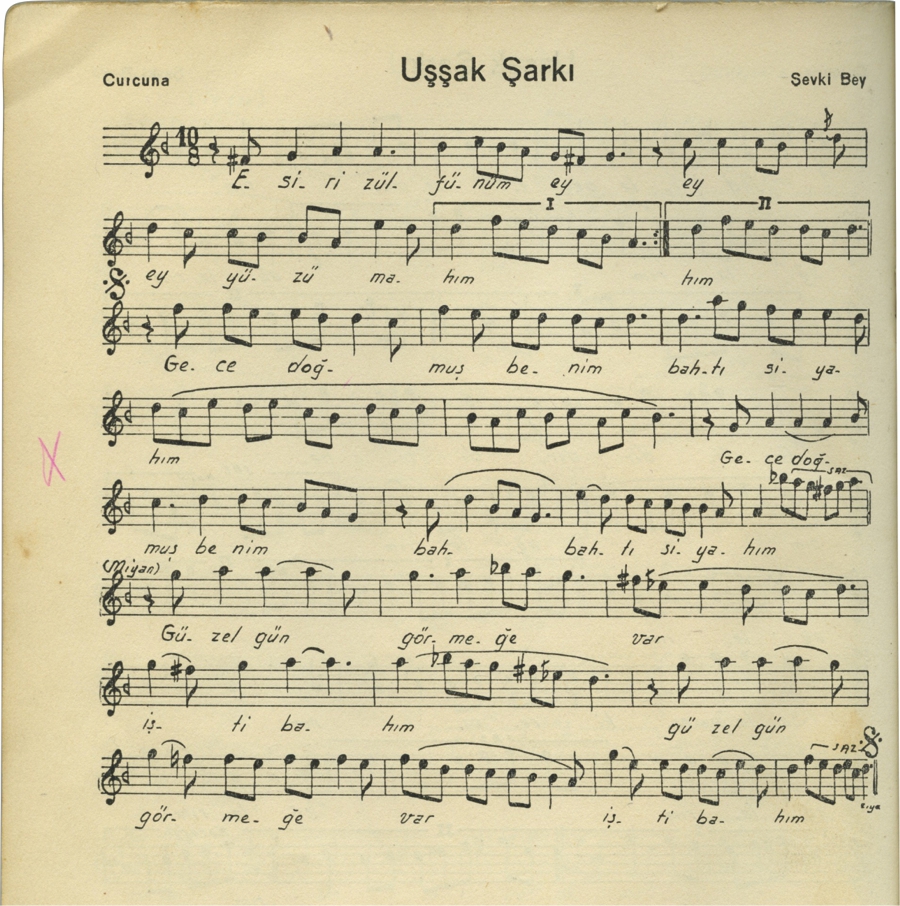

[5] Uşşak Şarkı «Esir-i zülfünüm ey yüzü mâhım»

Instrumentation: vocals (RS), clarinet (JH), violin (CO), ney (TH), oud (RR), kanun (WS), davul (RS). Mode: makam Uşşak. Meter: 10/8 (3 + 2 + 2 + 3), curcuna. Composer: Şevki Bey (1860–1891). Lyrics: Bahriyeli Vâsıf.

Şarkı (vocal form in Ottoman/Turkish art music), composed in İstanbul in the late 19th century. The lyrics are in Ottoman Turkish, which was basically the written language of the Ottoman elite. In terms of vocabulary, grammar and even symbolism, Ottoman Turkish borrowed extensively from Arabic and Persian. The poetic lyrics of songs like this one would have been difficult to understand to common speakers of Turkish at the time, and are close to being hermetic to modern Turks.

This is Čalgija’s first recording in this particular style. At first glance the song may seem to be a bit of an outlier, but it represents a natural extension of a repertoire that already included Turkish folk music and the related urban čalgija style (see [10]). However, while Čalgija’s repertoire was geographically and musically coherent, it was in fact highly unusual for one ensemble to play such a broad range of styles. It required the individual group members to play several instruments, adding up to a very eclectic set indeed.

Lyrics

Esir-i zülfünüm ey yüzü mâhım

Gece doğmuş benim baht-ı siyahım

Güzel gün görmeye var iştibahım

Gece doğmuş benim baht-ı siyahım

Firâkınla senin ey şems-i tâbân

Deminde görmedim bir ruz-i rahşan

Bana aşkın cihanı etti zindan

Gece doğmuş benim baht-ı siyahım

Translation

I am a prisoner of your hairlocks, oh, face like a moon

[You are] my black fate, born in the night

I doubt whether I will ever see a beautiful day

My black fate, born in the night

Since I am separated from you, oh radiant sun

Lately I have not seen a single bright day

My love for you turned my world into a dungeon

My black fate, born in the night

The version of ‘Esir-i zülfünüm ey yüzü mâhım’ that Čalgija used. Source: Taşçı, M. (1962) – Uşşak Faslı. İstanbul, Turkey: Marmara Matbaas, 63 pp.

[6] Žeravnenska răčenica | Жеравненска ръченица

Instrumentation: clarinet (JH), sopranino recorder (RS), violin (CO), accordion (WS), tambura (TM), tapan (TH). Modes: tempered forms of makam Hicâz, modulating back and forth to makams Karcığar and Nikrîz; sections in makams Rast and Hüseynî concluding with / modulating back via Kürdî. Meter: 7/16 (2 + 2 + 3), răčenica.

Beautiful dance tune from the village of Žeravna in eastern Bulgaria. In contemporaneous Bulgarian versions, the chord accompaniment will mirror the complexity presented by the melody’s many modulations, which are quite challenging harmonically. Čalgija does the exact opposite by using a Macedonian tambura (also see [2]) to merely accentuate the shifting tonic, putting more emphasis on modal structure and coherency.

[7] Ti kles, kaimeni Maria | Τι κλαις, καημένη Μαρία

Instrumentation: gajda (TH), violin (CO), kaval (RS), kanun (WS), santur (JH), tambura (TM), darabuka (RR). Modes: folkloristic forms of makams Nevâ, Hüseynî and Karcığar. Meter: 7/8 (3 + 2 + 2), kalamatiano.

Dance melody from Greek Macedonia, played by an unusual combination of North Macedonian and oriental instruments that may well have been the one that caught police attention during Čalgija’s field trip (see Čalgija at the turn of the 1980s). The title, ‘Why do you cry, poor Maria?’, refers to lyrics that can be sung to this melody, but not exclusively so; an online search for it will produce completely different melodies.

In fact, it is only since folk music became recorded that specific versions of songs gained an importance that they had never previously held. In the Balkans, you will find different combinations of lyrics, melodies and interludes as a natural result of music being propagated by oral transmission, even among peoples with different languages. The most famous example of this practice is a melody in makam Nivâvend that is best-known from the Turkish song ‘Üsküdar’a gider iken’ (On the way to Üsküdar), but which is sung all over the Balkans, the Middle East and beyond.

In Greek it is known as ‘Ichasa mandili apo xeno topo’ (Ήχασα μαντήλι από ξένο τόπο / I wore a scarf from a foreign place). The melody is used in the Albanian love song ‘Mu në bashtën tënde, të këndon bylbyli’ (In your garden, a nightingale sings). The words bashtë (garden) and bylbyl (nightingale), which are not used in modern Albanian, are derived from the Turkish words bahçe and bülbül, respectively. This shows that the Albanian version probably dates back to the Ottoman era; the same goes for [1] and [8].

Serbo-Croatian versions exist in South Serbia (Ruse kose curo imaš / Русе косе цуро имаш / Fair hair you have, girl), and Bosnia-Herzegovina (Oj đevojko Anadolko / Oh, Anatolian girl). The melody is used in the Bulgarian love song ‘Cerni oči imaš libe’ (Черни очи имаш либе / You have black eyes) and song of resistance ‘Jasen mesec več izgrjava’ (Ясен месец веч изгрява / A clear moon is already rising). The Macedonian version is ‘Oj devojče, devojče’ (Ој девојче, девојче / Oh girl, girl), and the Romanian one ‘De ai ști suflețelul meu’ (If you only knew my soul).

The acclaimed documentary film Whose is this song? (Adela Media, 2003) discusses its various Balkan versions. Less known is the fact that the melody even made its way to the Netherlands in the form of the St. Nicholas children’s song ‘Poets je elke dag wel je tanden?’ (Do you brush your teeth every day?). This must be the least poetic version that exists worldwide.

[8] Në Shkodër

Instrumentation: vocals (RS, JH), bağlama saz (TH), laouto (TM), accordion (WS), darabuka (RR). Modes: intro/interlude in tempered forms of makams Muhayyer and Karcığar, song modulates between tempered forms of makams Beyâtî, Acem and Acem-Kürdî. Meter: 9/8 (2 + 2 + 2 + 3).

Romantic song from the Shkodër area in Northern Albania. The instrumentation has been chosen to resemble a typical ensemble of that region, using the Turkish bağlama saz and Greek laouto to mimic the Albanian çifteli and sharkia lutes, respectively. This rather austere modal version of the song presents a contrast with the more modern version performed by Čalgija three years before [16]. One might argue that it also contrasts somewhat with the lyrics.

Lyrics

Në Shkodër ka ra nji dritë

ka l’shu rreze an’ o për an aman

Perenija t’ka goditë

kusur moj s’të ka lane

(2×)

O lujma lujma belin’e

ta fala quemerin’e

O lujma lujma shpinen’e

vera tu boft dimen’e

Kam e dorë bel e shpin’e

gushën farfuri aman aman’e

Zani jyt si gardalin’e

dhamët moj si inxhi

(2×)

O lujma lujma shtatin’e

ta fala sahatin’e

O lujma lujma doren’e

ta puthsha moj gojën’e

Ka lind dilli ka lind hana

flokt e art qindis aman aman’e

Bishtalecat nër gjylpana

të jan rrit moj n’ishtiharë

(2×)

O mos ma ngani ishën’e

se ma derdhi shishen’e

O mos ma ngani locën’e

se ma tremni gocen’e

Translation

In Shkodër a light has fallen

there was a ray of light from left to right

God has punished you

laden you with guilt

(2×)

Hey move, move your waist

away with your dress belt

Hey move, move your back

may your summer become winter

Leg and hand, waist and back

your porcelain neck

Your nightingale voice

your ivory teeth

(2×)

Hey move, move your body

l will give you a watch

Hey move, move your hand

may l kiss your lips

The sun rose, the moon rose

embroidering your golden hair

Pinned-up braids

grew in my dream

(2×)

Oh, don’t arouse me

for he poured me a bottle

Oh, don’t tease me, girl

because you will scare me off

[9] Selim bey | Σελίμ μπέης

Instrumentation: clarinet (JH), violin (CO), kanun (WS), oud (RR), laouto (TM), def (TH). Mode: folkloristic form of makam Uşşak. Meter: 3/2, tsamiko.

Dance named after Selim Bey, an 18th century Ottoman ruler of the Sanjak of Delvina, which corresponds roughly to Southern Albania and includes the northern parts of the Epirus region, from where the style and dance originate.

[10] Sardisale lešočkiot manastir | Сардисале лешочкиот манастир | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: vocals (RS, JH), violin (CO), kanun (WS), oud (RR), darabuka (RS). Modes: makam Rast modulating to makam Hüseynî. Meter: 28/4 (6 + 4 + 4 + 6 + 4 + 4), devr-i kebîr.

Ballad from the Macedonian čalgija repertoire, which appears to describe a ethno-religious incident in the Ottoman era between Slavic and Albanian inhabitants of Lešok and Slatino (Sllatinë in Albanian), respectively, two neighbouring villages in North Macedonia, close to the border with Kosovo.

Čalgija, or chalgiya, is an urban musical genre that is best-known from Macedonia (чалгија), but which also developed in Bulgaria (чалгия) and Serbia (чалгија). A typical čalgija ensemble (čalgii / чалгии) consists of clarinet, violin, oud or cümbüş, kanun and darabuka, a combination that is clearly not suited to play folk music in outdoor settings. So ‘urban’, other than having a certain level of refinement, implies that čalgija music is basically chamber music. Most of the original čalgija repertoire uses the Turkish makam system. It is modal, microtonal and uses no second voices or chord accompaniment. In all of these aspects, the čalgija style is closely related to Ottoman/Turkish art music, the urban style of İstanbul. In fact, the name relates to the Turkish word for musical instrument, çalgı.

For ‘Sardisale lešočkiot manastir’, such relationship is also evident from phrasing and rhythm. Its sections consist of 28 beats that, from a Western notation perspective, leave no choice but a division into 2/4 bars. However, this results in rather awkward 14-bar sections and chopping up the phrasing beyond recognition. What is actually played is two times 4 + 2 + 4 + 4 beats. While this may seem far-fetched and overly complex, it corresponds to one of the more common Ottoman/Turkish usuls (rhythmic cycles), devr-i kebîr, which appears to have made a rare appearance in the čalgija repertoire.

Altogether, čalgija stands for Wouter Swets’ approach to, understanding of, and appreciation for the music of the Balkans and Anatolia, which is why he used it as a name for the two consecutive ensembles he led between 1962 and 1995.

Lyrics

Сардисале, сардисале

лешочкиот манастир

Сардисале, сардисале

Арнаути Слатинчани

Кажи, попе, егумене

каде ти се комитите?

(2×)

А бре паша, кузум паша

јас комити не видох

(2×)

Се налутил турскиот паша

го запалил манастирот

(3×)

Transliteration

Sardisale, sardisale

Lešočkiot manastir

Sardisale, sardisale,

Arnauti Slatinčani

Kaži, pope, egumene

kade ti se komitite?

(2x)

A bre paša, kuzum paša

jas komiti ne vidoh

(2×)

Se nalutil turskiot paša

go zapalil manastirot

(3x)

Translation

They surrounded, they surrounded

the monastery of Lešok

They surrounded, they surrounded

Albanians from Slatino

Tell me father, abbot

where are your revolutionaries?

(2×)

Oh, pasha, dear pasha

I did not see the revolutionaries

(2×)

The Turkish pasha got angry

he set fire to the monastry

(3×)

Macedonian čalgija ensemble in a traditional line-up (LR): clarinet, violin, oud, darabuka and kanun. Sleeve image fragment, source: Ansambl Čalgija (1972) – Makedonska Ora Svira. Zagreb, Yugoslavia: Jugoton, EPY-34489, 1EP.

[11] Kopanica | Копанца | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: gajda (TH), gădulka (CO), kaval (RS), accordion (WS), tapan (RR), tambura (TM). Modes: folkloristic, tempered forms of makams Rast, Hüseynî, Nikrîz and Hicâz. Meter: 11/16 (2 + 2 + 3 + 2 + 2), kopanica.

Dance melody from western Bulgaria. Bulgarian folk music in general is renowned for its virtuosity and high performance standards (also see [17]). Leading performers will play highly complex melodies, rhythms and arrangements with a deceptive ease that has become a hallmark of their tradition. If you think of them as the Beatles, then Čalgija would be the Rolling Stones.

[12] Pia skyla mana | Ποιά σκύλα μάνα | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: vocals (RS), clarinet (JH), violin (CO), accordion (WS), oud (RR), laouto (TM), def (TH). Mode: tempered form of makam Sabâ. Meter: 3/4, tsamiko.

Čalgija’s version of this Greek song will have been derived from a transcribed or recorded original, but the currently best-known version is an a-metric, pentatonic Epirotic ballad (see [7] on lyrics-melody combination in Balkan folk music).

Lyrics

Ποιά σκύλα μάνα το ‘λέγε

τ’ αδέλφια δεν πονιούνται;

Τ’ αδέλφια σκίζουν τα βουνά

ώσπου ν’ ανταμωθούνε

Σαν κάμαν κι ανταμώσανε

σ’ ένα χρυσό τραπέζι

Χρυσά μαντήλια βγάλανε

τα δάκρυα σκουπίζαν

Καιρό που ‘χουν τα μάτια μου

να δούνε τα παιδιά μου

Είχα πολλά παράπονα

και κλάψανε μπροστά μου

Transliteration

Poiá skýla mána to ‘lége

t’ adélfia den ponioúntai?

T’ adélfia skízoun ta vouná

óspou n’ antamothoúne

San káman ki antamósane

s’ éna chryso trapézi

Chrysá mantília vgálane

ta dákrya skoupízan

Kairó pou ‘choun ta mátia mou

na doúne ta paidiá mou

Eícha pollá parápona

kai klápsane brostá mou

Translation

Which bitching mother was saying

that the brothers don’t feel for each other?

The brothers tear the mountains apart

until they meet

When they met

at a golden table

They took out golden handkerchiefs

they wiped their tears

My eyes, for a long time

haven’t seen my children

I had many sorrows

and they cried before me

[13] Kadıoğlu zeybeği | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: clarinet (JH), cura saz (CO), bağlama saz (TH), divan saz (TM), kanun (WS), darabuka (RR). Mode: makam Nikrîz. Meter: 9/2 (2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 3), ağır zeybek.

Dance melody from the Muğla province in southwest Anatolia. A zeybek (ζεϊμπέκικο / zeibekiko in Greek) is a slow dance from the circum-Aegean region, which can be danced by men and women, in groups or solo, and especially in the latter case there is ample room for individual expression.

[14] Kars’ın önü | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: gajda (TH), clarinet (JH), violin (CO), accordion (WS), tambura (TM), darabuka (RR), tapan (RS). Mode: lower register of makam Hicâz, intermittent Nişâbûr flavours. Meter: 9/4 (2 + 3 + 2 + 2).

The booklet of Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2 tells us that Wouter Swets took great pride in his ability to analyse complex meters and rhythmic patterns. However, what he wrote is so technical—and occasionally so harsh—that one forgets that joy and appreciation lay at the basis of his work. Swets’ music sheds more light on his tastes and preferences. For example, this folkdance melody from the Kars province in northeast Anatolia is quite simple, but uniquely effective in bringing to expression a powerful rhythm that Swets must have enjoyed greatly.

[15] Răčenica | Ръченица | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: gajda (RR), accordion (WS), tambura (TM), tapan (TH). Modes: Aeolian and Ionian. Meter: 7/16 (2 + 2 + 3), răčenica.

Bulgarian folkdance melody, played in the raunchy, high-energy performance style Čalgija’s concerts were famous for (also see [11]).

The heartland of he Ottoman Empire, Wouter Swets’ musicological canvas and frame of reference. Fragment of a map by Matthaeus Seutter (1727) – Magni Turcarum Dominatoris Imperium. Photo by Geograficus (NY), CC0 1.0.

[16] Në Shkodër | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: vocals (RS), clarinet (JH), violin (CO), accordion (WS), laouto (TM), def (RR). Modes: intro/interlude in tempered forms of makams Muhayyer and Karcığar, song modulates between tempered forms of makams Beyâtî, Acem and Acem-Kürdî. Meter: 9/8 (2 + 2 + 2 + 3).

[17] Dy të bukurat | Live concert recording, 1978 (mono)

Instrumentation: accordion (WS), violin (CO), laouto (TM), darabuka (RR). Mode: Aeolian. Meter: 5/8 (2 + 3).

Melody from Albania. The chords in Swets’ arrangement seem to draw from both Georgian polyphony and the Bulgarian-style harmonisation discussed in [2]. In socialist Bulgaria, state involvement in popular culture resulted, amongst other things, in well-trained composers and arrangers being tasked to elevate folk music to higher levels. Even though they will have had Western classical music in mind, their orchestral arrangements of traditional folk melodies and new folkloristic compositions are anything but Western in terms of harmonisation and chord progression.

As demonstrated by many rather uneasy or downright cheesy results, a purely Western-style harmonisation—whether it be jazzy or classical—doesn’t mix well with the modal structure of the traditional styles found in the Balkans. The main problem seems to be that the two are fundamentally different in terms of phrasing, structure and sense of conclusion. Contemporary modal music composer Ross Daly argues that Eastern modality and Western harmony have followed diverging pathways for too long to be easily combined, but that the Bulgarians may hold the key to further explore the possibilities that their combination may offer. Swets’ arrangement of Dy të bukurat is an example of their application to Albanian music.

‘Dy të bukurat’ means ‘the two beauties’; its melody is somewhat similar to ‘Nji ditë diele’ [1]. This makes it a perfect piece to bring this album to a conclusion.

Other releases by Čalgija

- Unforgotten / PAN 2056 / TouMilou #4, 2020 / album

- Vintage Recordings (1964–1966) / TouMilou #2, 2017 / EP

- Mosaique Vivant / MV695, 1995 / compilation album with three tracks by Čalgija

- Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2 / PAN 2007CD, 1991 / album

- Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #1 / MU 7425, 1978 / PAN 7425, 2013 / album