Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #1 | Liner notes

Introduction

Čalgija

The ensemble Čalgija was formed in Utrecht in 1969 by ethnomusicologist Wouter Swets using Dutch musicians whose object was to play folk music from the Balkans and Anatolia in the manner characteristic of the authentic living expression of this music by professional musicians in the countries themselves. Čalgija takes its name from the typical ‘alla turca’ ensembles which have arisen in the Macedonian towns since the nineteenth century and likewise have a general Balkan-Turkish repertoire.

Living folk music is always in motion; it continuously changes form and adapts itself so that it can continue to fill its spontaneous communicative role in society where circumstances change. The renovating forces are, however, continually kept in check by inspiration from the tradition. From wherever you are in the world, today always lies between the past and the future and links the two together.

Where folk music is modified in such an unbridled fashion that the good traditions are thrown out with the bad, as happens for instance when it becomes commercialized, it will sooner or later find itself completely uprooted. If, on the other hand, it becomes the victim of purists who want to preserve its authenticity and thus latch on to its past, it degenerates into a museum piece.

Like the local ensembles, Čalgija wants, without falling into either of these extremes, to contribute to such development in the folk music of the Balkans and Anatolia that a feeling for tradition and an extension of the possibilities by means of experiment go hand in hand. The repertoire on the record, for the most part folk-music tunes, bears witness to that. A reconstruction of a traditional performance [8] is thus heard alongside a completely new, original arrangement of a well-known Turkish song for two bagpipes and a large drum [11]. In addition, there is a new technique of playing the Macedonian bagpipe developed by Tjarko ten Have, which makes it possible to use more chromatic tones, so that in future melodies which used to be unsuitable can also be played on this instrument [4].

Often, traditional instruments are combined with western instruments in so far these have become fashionable locally [1, 4, 5, 9], completely in keeping with the local situation. Use is even made of a kaval made from plastic electricity conduit, copied from a wooden Bulgarian example by Roel Sluis and producing a near enough identical timbre. It is played here by Tjarko ten Have [8]. Alongside this, however, in spite of innovations and perfecting, the traditional style, manner of performance and timbre characteristic for each area remain fundamentally recognizable.

As a result of this all the listener will hear Balkan and Turkish music, which on the one hand sounds much more traditional than the usually commercialized tunes on local labels, but on the other hand contains quite new elements, not yet adopted by the local musicians. Because living folk music always arises spontaneously from an oral tradition, complete or added improvisation plays an essential role. In principle, therefore, Čalgija only employs those forms of ensemble playing that allow for a certain amount of room for individual variation and ornamentation.

Čalgija around 1978. Front row (LR): Remco Busink, Wouter Swets, Thijs de Melker, Jan Hofmeijer; back row (LR): Roel Sluis, Tjarko ten Have, Crispijn Oomes, Roelof Rosendal. Photo: Remco Busink.

Musicians

- Remco Busink—tambura [1, 3, 7, 9]; outi [8]; laouto [6]; bağlama [2]

- Tjarko ten Have—Macedonian gajda [1, 4, 9, 11]; gavala [8]; bağlama [2, 5]; defi (def) [6, 12]; tăpan [7, 10]

- Jan Hofmeijer—vocals [3]; Macedonian gajda [11]; clarinet [1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 12]; santouri [8]

- Thijs de Melker—tambura [1, 3, 7, 9]; divan sazı [2]; llaute [12]; guitar [6]

- Crispijn Oomes—violin [1, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12]; gădulka (kemene) [3, 7, 9]; cura saz [2]

- Roelof Rosendal—Bulgarian gajda [7]; tarabuka (darbuka toumbeleki [1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9]; davul [11]

- Roel Sluis—vocals [3, 5, 9]; kaval (gavala, ney) [1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10]

- Wouter Swets—kanun (kanonaki) [2, 8]; accordion [1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12]; tăpan [3]

Local instruments used

- Kaval (gavala)—long open flute from the Balkans

- Ney—long open flute from Turkey

- Gajda—bagpipe from the Balkans

- Tambura—Bulgarian and Macedonian 4-stringed long-necked lute

- Laouto (llaute)—Greek and Albanian 8-stringed, short-necked lute

- Outi (oud)—oriental 11-stringed, short-necked lute

- Cura saz—small Turkish 6-stringed, long-necked lute

- Saz (bağlama)—Turkish 6-stringed, long-necked lute

- Divan sazı—large Turkish 6-stringed, long-necked lute

- Kanun (kanonaki)—oriental zither

- Santur (santouri)—oriental dulcimer

- Gădulka (kemene)—Bulgarian and Macedonian pear-shaped, 3-stringed fiddle

- Tăpan (davul)—Balkan and Turkish large drum

- Defi (def)—Balkan and Turkish tambourine

- Tarabuka (darbuka, toumbeleki)—oriental vase-shaped drum

Čalgija’s instruments (LR). Against wall: oud, violin, clarinet, Bulgarian kaval, PVC kaval, Turkish kanun. On the table: bağlama saz, cura saz, gădulka. In front of table: def, darabuka, Persian santur; tapan to the right. In the front: three gajdas (two Bulgarian, one Macedonian). Not shown: accordion, divan sazı, laouto, Macedonian tambura, ney. Photo: Eelco Brinkman.

Pronunciation

A guide to the correct pronunciation of the Serbo-Croat, Bulgarian, Greek and Turkish words appearing in the sleeve notes:

a—the ‘a’ in the North English pronunciation of ‘man’

ă—the ‘u’ in ‘cut’

c (Serbo-Croat, Bulgarian, Macedonian)—the ‘ts’ in ‘itself’

c (Turkish)—‘j’ as in ‘jam’

č—‘ch’ as in ‘church’

ć—as above, but with the tongue further forward in the mouth

dh—the ‘th’ in ‘the’

e—the ‘e’ in ‘rest’

g—the ‘g’ in ‘goal’

ğ (between o and l)—an aspired ‘g’

ğ (between o and l)—an aspired ‘g’

h (Serbo-Croat, Bulgarian, Macedonian)—the ‘ch’ in the Scottish ‘loch’

i—the ‘i’ in the French ‘quitte’

ı (undotted i)—the ‘u’ in ‘cut’

j—the ‘y’ in ‘year’

o—the ‘o’ in ‘hot’

ou—the ‘u’ in ‘push’

s—the ‘s’ in ‘soap’

š—the ‘sh’ in ‘sheep’

ş—the ‘sh’ in ‘sheep’

sh—‘sh’ as in ‘sheep’ (Albanian)

u—the ‘u’ in ‘push’

ü—the ‘ü’ in the German ‘Tür’

v—the ‘w’ in ‘water’

y—the ‘y’ in ‘year’

z—the ‘z’ in ‘zeal’

ž—‘g’ as in French ‘genre’

- Track numbering: the original LP track numbers A1 though A6 (a-side) and B1 through B6 (b-side) have been renumbered [1] through [12].

- Geographical denotations: references to Yugoslavia and its constituent republics (1943–1992) have been updated to the current political situation.

- Transliteration: the Bulgarian Cyrillic hard sign Ъ/ъ is romanized as Ă/ă instead of with an apostroph.

Impact and spin-off:

- The title track of the award-winning album The Sensual World (EMD 1010, 1989) by British art rock singer Kate Bush (1958) uses Wouter Swets’ arrangement of ‘Antice, Džanam, Dusiče’ [4] as a countermelody.

- Irish musicians Andy Irvine (1942) and Davy Spillane (1963) based their versions of ‘Sulejmanovo oro’ and ‘Antice, Džanam, Dusiče’ on the highly acclaimed fazz-folk fusion album EastWind (TARA CD 3027, 1992) on Wouter Swets’ arrangements of these pieces [1, 4].

- Čalgija would record another version of ‘Haj, otkako je Banja Luka postala’ [5] in 1995 with singer Abida Ćelović-Kljuno for the sampler album Mosaique Vivant (MV695, 1995).

Michiel van der Meulen

Bunnik, July 2022

Front cover art: ‘Two Turkish men drinking tea’ (1978) by Tjarko ten Have (1947–2003); oil on canvas, approx 75 x 65 cm, privately owned. Photo: Jaap van Beelen (2022).

Track notes

[1] Sulejmanovo oro

A folk dance in 11/16 time (2 + 2 + 3 + 2 + 2) from Aegean Macedonia, North Greece. Instruments used: gajda, kaval, tambura (2), violin, clarinet, accordion, and tarabuka.

The title of this folk dance means literally ‘Sulejman’s dance’, and originates from the fact that the melody used is that to a folk song in the Macedonian language which begins with the words ‘Sulejman aga imal dvanajset čiflici’ (i.e., ‘Sulejman aga had twelve pieces of land’). The song comes from around the town of Edessa, which used to have the Macedonian name Vaden, and it concerns a Turkish landowner Sulejman, who owned twelve pieces of land, three thousand sheep and as many goats, but did not want to surrender the girl Lena, who worked for him on the land, to her lover because she was so beautiful. Of course this was something which the lover would not take, and he attempted to escape from ‘the tyrant’ with Lena.

The content of this song refers to the period 1389–1912 when Macedonia was under Osman rule and the Macedonian farmers were forced to work as serfs on the land appropriated by the Turkish landowners. Now there are no longer any Turks living in the Greek part of Macedonia. After 1922 their place was taken by even more Greeks from Turkey. Because of this and other exchanges of people before the Second World War the number of Greeks increased, whereas the Macedonian-speaking population gradually became a small minority, living mainly in the N.W. part of Aegean Macedonia. Macedonian, which is most akin to Bulgarian, is still spoken in Pirin Macedonia, now a part of Bulgaria.

During the Greek Civil War of 1943–1949, many Macedonians, also for nationalistic reasons, chose the side of the communists against the Greek government. Nowadays, more and more Macedonians in Greece are switching to the Greek language. In order to avoid political difficulties at village festivals, the songs with Macedonian words are either played instrumentally, or sometimes translated into Greek, or even provided with new Greek lyrics.

The version of Sulejmanovo oro on this record is a rhapsodic adaptation by Wouter Swets, in which the song about Sulejman forms the central theme, alongside other dance melodies from the same region. So, what we have here is, as it were, a fixed form of something which is improvised on the village square when, during a dance which lasts longer than expected, the musicians introduce new dance melodies to give some variation—melodies which must, of course, be in the same time. In this case it is the typical Macedonian 11/16 time, with the pattern 2+2+3+2+2.

In this recording, the melody of the Sulejman song is heard first, and is played twice, after which an interlude paves the way for the transposed reappearance of the melody. In another interlude, the tempo is gradually speeded up, after which a new dance melody is heard, namely that of the ‘Stankino oro’ (‘Stanka’s dance’, where Stanka is the name of a girl). An improvised interlude then follows, after which the dance tune ‘Buče ti razvile’ is introduced. Following a last interlude, the Sulejman melody finally returns once more in a changed form, and a typical bagpipe cadence finishes the piece.

With the exception of a few interludes, which have been composed by Wouter Swets in Aegean Macedonian style, everything in this rhapsody is the result of rearrangement of musical material recorded during a field-recording trip made to Macedonia in 1964.

[2] Kerimoğlu zeybeği

A folk dance in 9/2 time (3+2+2+2) from South-West Anatolia (vilayet Muğla), Turkey. Instruments used: kanun, cura saz, baglama (2), divan sazı, clarinet, and darbuka.

Zeybek dances are characteristic of West Anatolia, and in particular of the Aegean coast of Turkey. They are usually in 9/4 or 9/2 time, with the pattern 3+2+2+2 or 2+2+2+3, and are characterized by a bravura which is at the same time both lumbering and stately, slow and fiercely heroic.

The part of Turkey on the Aegean coast has many historical and cultural links with the Greek islands Mytilene (Lesbos), Chios and Rhodes which lie just off it, where the same folk dance, under the name zeibekiko, is popular. This latter should not, however, be confused with a dance on the Greek mainland having the same name and the same metre, which forms part of the composed rebetika or bouzouki repertoire of the large cities and must be considered a popular degeneration of the original folk dance.

In the example on the record, the zeybek melody gradually descends from the octave to the final note on the first degree using a minor scale with sometimes a neutral sixth and continually a neutral second, resulting in ¾-tone intervals. This is reminiscent of the makam (i.e., mode) Muhayyer in Turkish classical music.

[3] Jovino horo

A folk-dance song in 18/16 time (3+2+2)+(2+2+3+2+2) from Šopluk, a region in West Bulgaria which continues into East Serbia and is populated by the Šop people. Instruments used alongside the vocals: kaval, gajda, gădulka, tambura (2), and tapan.

Dances of this type can also be performed in 14/16 time without altering the steps. The only difference is in the relation of the lengths of the dance movements to each other: (3+4)+(2+2+3+4) becomes (2+3)+(2+2+2 + 3).

In the Serbian part of Šopluk, the Bulgarian Jovino horo has the counterpart Jelkino kolo. The lyrics in both cases deal with the same subject, but the evil-doer in Bulgaria is Jova and in Serbia Jelka:

Povela e Jova, lele, dva konja na voda

Jove mala mome, lele, Jova mala mome

Pa si edin poji, lele, s voda razm’tena

A drugija poji, lele, s voda izbistrena.

Što si konja poji s voda razm’tena

Tozi i je konja na miloto brače

Što si konja poji s voda izbistrena

Tozi i je konja na miloto libe.

Translation:

Jova has fetched two horses to give them water,

Oh Jova, little girl, Jova, little girl,

She gives one cloudy water to drink

But she gives the other clear water.

The horse to which she gives cloudy water to drink

Is her dear brother’s horse,

The horse to which she gives clear water

Is her dear lover’s horse.

The melody used on the record is a lesser known but fine version, which uses a minor second and a major third in its scale in place of the usual major second and minor third. The interlude was composed by Wouter Swets.

[4] Antice, džanam, dušice

A folk-dance tune in 7 /8 time (3+2+2) from Kičevo, North Macedonia.

This is an instrumental interpretation of a completely new form, in which the traditional Macedonian gajda, or bagpipe, is played in an original fashion and combined with the modern accordion. The gajda has a drone on B while the melody played on the chanter has a range of an eleventh, from D-sharp to G, and uses many chromatic tones. The accordion adds an extra drone on E, the fifth below the B of the gajda, and generally plays the melody in parallel lower thirds. The kaval duplicates the melody of the gajda, while the tarabuka takes care of the rhythmical accompaniment. The interlude has been composed by Wouter Swets in Macedonian style.

The lyrics of this song concern a very attractive girl who is kept subordinate to her younger sister by her parents, so that she doesn’t find a man.

[5] Haj, otkako je Banja Luka postala

A love-song from Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzogovina. Instruments used to accompany the vocals: saz, accordion, clarinet and tarabuka.

During the centuries of domination by the Turks (1463–1878), many Bosnians, in particular the nobility and townspeople, changed to Islam, but continued to speak their own Serbian language. Through this change of faith, but also through their education and through the fact that the Turkish administration was set up in the towns and the Turkish garrisons were situated there, they easily came into contact with the refined Osman culture of İstanbul, which strongly influenced their songs. Thus, for instance, the melody of the song recorded here clearly carries the stamp of Osman classical music from İstanbul, the city from which the melody probably originates.

An indication of this is the fact that in Bulgaria, where a different version is particularly well-known in the towns (!), the lyrics mention İstanbul: ‘Văv Carigrad beglika se prodava’ (i.e., ‘In İstanbul the title Bey is sold’).

Furthermore, the course of the melody of this song corresponds completely with the makam (i.e., mode) Hicâzkâr in the classical Turkish music of İstanbul. There is undoubtedly talk of a so-called Gesunkenes Kulturgut, in other words a classical composition carried down to the level of the folk, there to become common property and live on in a more or less adapted or corrupted form.

In the version on this record, Wouter Swets composed the interlude which separates the various sung couplets from each other in makam Hicâzkâr, with a transient reference to makam Kürdilihicâzkâr. The lyrics are as follows:

Haj otkako je Banja Luka postala,

aman aman postala

Haj nije ljepša udovica ostala,

aman aman ostala

Haj, kao što je Džanfer bega kaduna,

aman aman kaduna

Haj, nju zaprosi Sarajevski kadija,

aman aman Kadija

Haj, ona neće Sarajevskog kadiju,

aman aman Kadiju

Haj ona hoće Banjalučkog deliju,

aman aman deliju

Translation:

Hey, even since Banja Luka came into being, oh, oh, came into being,

Hey, never has there been a more beautiful widow left behind, oh, oh, left behind.

Hey, for just as if it were the wife of Džanfer Bey, oh, oh, that lady,

Hey, (even) the judge of Sarajevo is after her, oh, oh, the judge.

Hey, but she doesn’t want the judge of Sarajevo, oh, oh, the judge,

Hey, she wants the playboy of Banja Luka, oh, oh, the playboy.

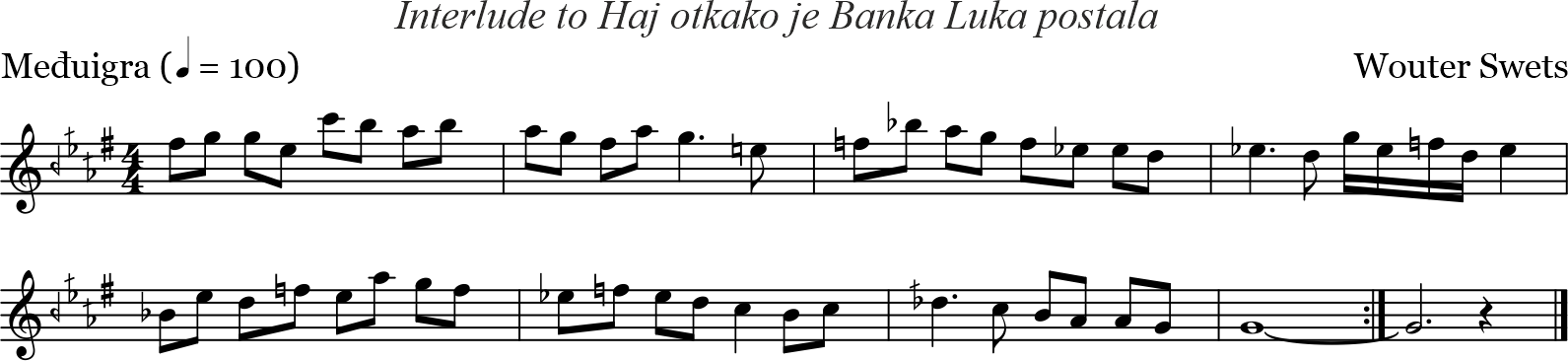

Interlude to ‘Haj, otkako je Banja Luka postala’ composed by Wouter Swets, reproduced, with permission, from his handwritten manuscripts; the Turkish Arel-Ezgi system was used instead of the original western equal-tempered notation. Copyright rests with the composer.

[6] Papadhia

A folk dance in 5/4 time (2+3) from Epirus, North-West Greece. Instruments used: clarinet, violin, accordion, laouto, guitar, and defi.

[7] Lukovitski momi horo

A folk dance in 6/16 time (2+3) from the district of Loveč, North Bulgaria. Instruments used: gajda, kaval, gădulka, tambura (2), accordion, and tapan.

This dance comes from an area occupied by Pomaks, in other words Bulgarians who changed to Islam during the Turkish domination. In contrast to the Mohammedan Bosnians, these Pomaks were out to preserve their own ancient culture and customs—something in which they were often more successful than their fellow Bulgarians who had remained Christians, in view of their privileged position within the Osman empire.

Being in 5/16 time, the dance is of the type pajduško horo, which is found a great deal in North Bulgaria but is also known outside that region. Thus, different dancing and singing to the melody of the folksong ‘Lukovitski momi’ (i.e., ‘Girls from Lukovit‘) can be found in the Vardar-Macedonia region. There the dance melody has the name ‘Makedonka’.

[8] Kostantis

A folk dance in 4/4 time from Aegean Thrace, North-East Greece. Instruments used: gavala (2), violin, kanonaki, eastern santouri, outi, and toumbeleki.

In making the recordings for this album, the standpoint taken was to record as far as possible only that which wasn’t available on any other western label. In this case, however, a departure was made from this standpoint in order to draw attention, by means of a reconstruction, to a beautiful authentic method of performing which, it would appear from the recording of Kostantis on Arion ARN 33 286 (Side A, Track 4), is being lost.

The harmony on the laouto in the Arion recording doesn’t combine well with a melody from the Byzantine–Osman tradition which was unmistakably intended to be monophone, while the rhythm on the toumbeleki is played in far too elementary and scholastic a fashion. In the recording on this album, harmonization has been foregone deliberately, in order to allow the melody, in the classical Turkish makam Hüseynî, to come completely into its own; elaboration of the schematically given rhythm is improvised. In addition, use was made of the eastern santouri (in vogue in Thrace before the introduction of the western-produced santouri there), because it is only on this instrument that the ¼-tone intervals in the Kostantis melody can be played.

[9] Liljano mome ubavo

A folk-dance song in 11/16 time (3+2+2+2+2) from Bitola, North Macedonia. Instruments to accompany the vocals: kaval, gajda, kemene, tambura (2), clarinet, accordion, and darbuka.

Nowadays, partly under the influence of commercial tendencies, this song is often sung in two-part harmony, with the second voice continuously accompanying the first in parallel lower thirds. This gives rise to the effect that the melody is in a major key but ends on the upper third of the tonic. In this recording, the accompaniment consists mainly of a a drone from the gajda, a twelfth below the final note of the song, so that the melody acquires a true modal significance. The metrical pattern of this dance tune is characteristic of West Macedonia (both the North Macedonian and Greek parts).

The lyrics of the song are as follows:

Liljano mome ubavo, Liljano pile kalešo

Ušte li moma ke odiš, ušte li svetot ke goriš (2×)

Na stari glavi vnučinja, na mladi nevesti momčinja

Žena i deca ostavam, tebe Liljano da zemam (2×)

Nemoj Liljano, ne čini, ne ostavaj rana na srce

Celovek jas ke ti sluguvam, tebe Liljano da zemam (2×)

Translation:

Liljana, beautiful maid, gay chicken,

Must you always go out, must you still always set the world on fire?

For the old ones there are grandchildren, and for young brides marriageable fellows.

But for you, Liljana, I would leave my wife and children.

Do stop that nonsense, Liljana, don’t give my heart pain,

I will always serve you, you’re the one I want Liljana.

[10] Kars yerli barı

A folk dance in 10/8 (3+2+2+3) and 6/8 time from Kars, North-East Anatolia, Turkey. Instruments used: ney, clarinet, violin, accordion, and davul.

The vilayet Kars borders Transcaucasia, and before 1923 it was for about half a century a part of the Russian Czardom. It is because of this that western instruments like the clarinet, violin and accordion could be adopted there, and are very common in the local folk music, which is strongly inlfluenced by the Armenians, the Kurds, and the Azeri-Turks from Azerbaijan. The davul is played by hand in this recording.

Kars yerli barı means literally local bar (i.e., a particular form of folk dance) from Kars. Dances in 10/8 and 10/16 time, with the pattern 3+2+2+3, are found a great deal in East Anatolia, Kurdistan, Armenia and Azerbaijan.

[11] Osman Paşa

An instrumental interpretation of a folk dance in 6/4 time from Turkish Thrace (Rumelia, European Turkey). Instruments used: gajda (2), and davul.

In 1877 the fortress Pleven in North Bulgaria, not far from the river Danube, was strongly defended by the Turks, under the leadership of Osman Paşa, against the Russians who, in spite of their greatly superior force, were only able to take the town after a long siege. This so captured people’s imagination that the Turkish composer Mehmet Ali Bey wrote a song commemorating the event. ‘Tuna nehri’ (i.e., ‘The river Danube’) became universally popular and was accepted as a folk song. Here and there, people also began to dance to it. In the Greek part of Thrace it is used as a wedding tune. In Macedonia and Albania there are versions of the song’s melody in another time and with other lyrics. One can even find what once began as Osman Paşa in the liturgy of a Christian monastery near Mardin in South-East Anatolia. New is the instrumentation of this melody by Wouter Swets for two Macedonian bagpipes used in an unusual way.

[12] Valle nr. 1 e Tiranës

A folk dance in 7/8 time (2+2+3) from Tirana, Albania. Instruments used: clarinet, violin, accordion, llaute, and def.

This dance is of a type that in that part of Vardar-Macedonia bordering on Albania is known as Toska, or dance of the Tosks, South Albanians. While it is true that Tirana itself lies in the region of the Gegs, North Albanians, a land’s capital attracts people from everywhere and as such promotes acculturalization processes. This is further evidenced by the musical rhapsodic framework of this dance in which the typical South Albanian idiom dominates initially, later to make room for idioms originating from other regions of the country or even Macedonia and Greece.

Other releases by Čalgija

- Üçayak / TouMilou #5, 2021 / album

- Unforgotten / PAN 2056 / TouMilou #4, 2020 / album

- Vintage Recordings (1964–1966) / TouMilou #2, 2017 / EP

- Mosaique Vivant / MV695, 1995 / compilation album with three tracks by Čalgija

- Music from the Balkans and Anatolia #2 / PAN 2007CD, 1991 / album