Ariadne | Liner notes

Introduction

Ariadne features a selection of live tracks recorded in the garden of Labyrinth Musical Workshop in Houdétsi, Crete. The workshop was named after the maze that the mythological king Minos of Crete used to keep the Minotaur, a creature with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. Every nine years, a group of fourteen young Athenians, handpicked by their king Aegeus, was sent into the labyrinth to be devoured by the Minotaur as retribution for the death of Minos’ eldest son, Androgeus, in Athens.

To break this cycle, Athenian prince Theseus volunteered to join the sacrificial group and kill the Minotaur. Minos’ eldest daughter, Ariadne, who was put in charge of the labyrinth, fell in love with Theseus immediately after he set foot in Crete. She provided him with a sword to kill the Minotaur and a thread to help him retrace his steps out of the maze. In return for her help, Ariadne made Theseus promise to marry her and take her to Athens, where they could escape Minos’ wrath. However, after the deed was done and the couple fled from Crete, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos.

This album emerged from the current Cretan Labyrinth in a much more peaceful and fortunate way and is named after the true hero of this rather grim myth, without whom the Minotaur would not have been defeated. Five of the compositions previously appeared on the studio albums Európe and Erato, and two are new. The EP is a lively excerpt of the full concert, conveying the atmosphere and energy of the evening, and adding something to the studio renditions of the repertoire.

Michiel van der Meulen

Brussels, November 2024

‘Ariadne in Naxos’ (1898, oil on canvas, 91 x 133 cm) by Evelyn de Morgan (London, 1855 – London 1919).

Track notes

[1] Hebros / Hüseynî karşılama

First release: Európe (2019) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Hüseynî | Usul: aksak (9/8, 2-2-2-3) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Michiel van der Meulen (tambura), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (bendir)

Hebros is the ancient Greek name for the river that is now called Maritsa (Марица) in Bulgaria, Evros (Έβρος) in Greece and Meriç in Turkey. Its catchment spans most of the larger Thrace region, where eastern modality and western harmony meet and mix beautifully. The river used to connect Byzantium with Middle Europe as a trade route, but recently got to be known abroad mainly as an obstacle for Middle-Eastern refugees on a northern route to Europe. Unfortunately so. [Full original track notes]

[2] Barbanera / Nihâvend evfer

First release: Európe (2019) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Nihâvend | Usul: efver (9/8, 2-2-2-3) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (kudüm)

The Iberian peninsula […] is the second great European mixing zone of western and eastern musical idioms, the relative proportions of which roughly correlate with the duration of Moorish rule. The name of this piece, Barbanera (‘Blackbeard’), plays with that idea, referring to both Hayrettin Paşa, nicknamed Barbarossa, the much feared red-bearded Ottoman admiral who frequently raided Spain from North-Africa, and Christos Barbas, a much admired musician who actually managed to conquer Spain – with modal music, that is. It was Christos I was studying with when I wrote this piece. He has no nickname I know of but is distinctly black-bearded. [Full original track notes]

[3] Propontis / Phrygian metal

Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Mode: Phrygian | Metre: 4/4 (sousta) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (bendir)

The rhythm of this composition echoes a Cretan sousta, raw power traditionally administered by the laouto. The mode and modulations were inspired by a piece of music from the Crimean Tatars. Though I have forgotten the specific piece, I am constantly reminded of its region of origin, which has once again been annexed. Descriptions of Crimea often highlight its so-called strategic position in the Black Sea, implying that its occupation brings significant military advantage. This rather circular definition of military strategy illustrates how power ultimately serves only itself.

The name Propontis encapsulates the two sources of inspiration for this composition geographically. It is the ancient Greek name for the Sea of Marmara, the inland sea between Turkey’s European territory and its Asian mainland, connecting the Aegean and Black Seas.

~ ~ ~

This version of Propontis, with two repetitions that build in intensity, reminds me of a geographically unrelated encounter with a pack of Maremma sheepdogs while doing geological fieldwork in the Sibillini Mountains in Central Italy during the late 1990’s. These dogs are a local breed: white, fluffy, and with a friendly appearance, resembling a golden retriever or some other adorable pet featured in toothpaste or laundry detergent commercials. So, when six of them started running toward me from a distance, I first thought little of it and expected a standard display of canine enthusiasm, with them drooling on me being the greatest risk.

The first time the piece is played represents me still being optimistic. The first repetition, when the oud begins strumming the sousta rhythm, represents my realisation that the dogs weren’t friendly at all. With their teeth bared and unusually quiet while running as fast as they could, it became clear they were not simply happy to see me. They were on the hunt.

Normally, I don’t let myself be intimidated by medium-sized furry animals, especially when I’m carrying a geologist’s hammer. However, as these particular ones closed in, I started to consider myself lucky to be standing next to my car. I waited while losing my bravado. When the dogs got really close, I chose safety over pride and got into my car, a red Citroën BX, slamming the door just seconds before they arrived.

The second repetition, with the oud and bendir grinding, the bass growling, and the flute, violin and cello howling, represents the dogs attacking the car: their teeth scraping the metal, barking frantically, circling around, and jumping against it. I decided to move to another location and drove off while the dogs continued trying to maul my vehicle. I passed the shepherd, who was sitting by the road doing nothing. I honked angrily. He ignored me completely. The piece ends.

Years later, I passed through the same area with my wife. To my amazement, I saw the same shepherd with a pack of the same dogs. “Look, such nice dogs!”, she said. I said that these were the very ones I had been telling her about. “OK, let’s drive on.”

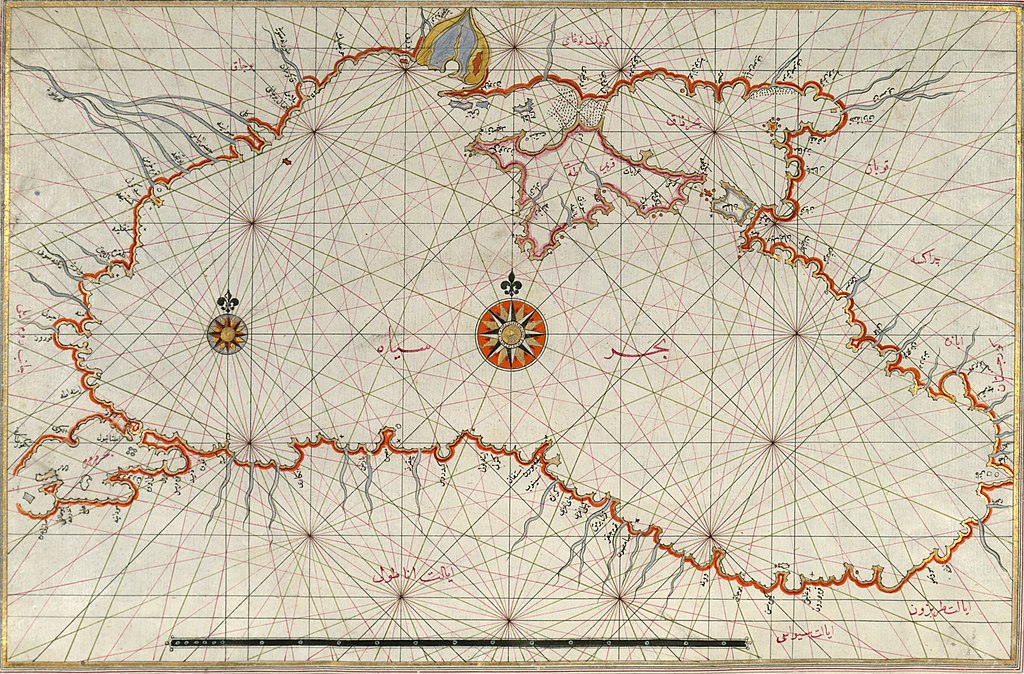

Map of the Black Sea (1525) by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Pîrî Reis (1465?–1553). Ink and pigments on laid paper, 36 × 66 cm.

[4] Kilim / Janino

First release: Erato (2022) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Uşşak | Metre: 18/16 (3-2-2-2-2-3-2-2, janino) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (kaval), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Michiel van der Meulen (tambura), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (bendir)

The rhythm of ‘Kilim’ is inspired by a type of south Slavic dances in an 18/16 metre counted as 3-2-2-2-2-3-2-2 (Bulgarian jove male mome / Macedonian janino). This rhythm got to me when producing the album Unforgotten by Čalgija (Pan 2056 / TouMilou #4), which has two pieces using it. The name kilim (Middle Eastern rug) was loosely inspired by the piece’s close-knit structure and its syncopation. [Full original track notes]

[5] The Rose and the Nightingale / Phrygian phantasy

First release: Erato (2022) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Mode: Phrygian | Usul: sengin semâî (6/8, 3-3) and yürük semâî (same metre, faster) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (kudüm)

The rose and the nightingale […] are important metaphors in Eastern poetry. The nightingale can be considered a counterpart of Shakespeare’s Romeo. He will suffer and neglect himself for the love of the rose, which some poets described as the blood springing from his wounded heart. The rose stands for unattainable love, as symbolised especially by her thorns, which may however also offer the nightingale protection against his mortal enemy, the snake. The rose wouldn’t be as famous as a symbol of love if it weren’t for the nightingale’s songs about her. The piece has a contemplative first part and stronger second, which could represent a fragrant rose and an anguished nightingale, respectively. Conversely, they could also stand for the nightingale singing and the rose stinging – it is up to you to decide which is what. What matters is the contrast between the parts, the shared theme, and the peaceful ending. [Full original track notes]

[6] Nazar / Hüseynî mandıra

Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Mode: folkloristic forms of makam Hüseynî | Metre: 7/16 (2-2-3, mandıra/mandilatos/răčenica) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (kaval), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Michiel van der Meulen (tambura), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (bendir)

In the summer of 1999, my wife Martine and I travelled to Greece with a very dear friend, the Greek palaeontologist Kostas Theocharopoulos (1966–2001). He had been staying with us to finalize his PhD thesis. Due to health problems that would later turn out to be serious, Kostas had gotten stuck, so palaeontologist Hans de Bruijn (1931–2021) and I decided to invite him to the Netherlands to help him get back on track.

Three weeks of hard work at Utrecht University paid off; the thesis manuscript was finished, and ready to be printed and distributed to the thesis committee. My wife and I were invited to accompany Kostas back home, meet his family, and rest a bit. We were looking forward to the trip, but his health problems—terrible migraines—were still troubling him, even though a Dutch GP had insisted they were caused by the stresses of his work. Our stay with Kostas’ family would mark the beginning of a lifelong friendship, but it was overshadowed by his rapidly worsening condition. After a couple of days, he had to be rushed to a hospital, where the cause of his migraines became apparent.

In a contrast that was almost impossible to digest, our hosts saw their world falling apart, while, at the same time, life seemed to smile at me. I had just graduated with a PhD in geology, Martine was pregnant with our son Tom (2000), and upon our return, I would begin my first job at a road and hydraulic engineering institute. Under these almost schizophrenic circumstances, I remember a few occasions when Kostas’ mother, Sofia, would murmur something I couldn’t quite understand while making the sign of the cross in Martine’s direction. When I asked about it, Kostas explained that she was averting the evil eye.

According to Eastern Mediterranean beliefs dating back to antiquity, there is such a thing as too much luck. The evil eye represents the type of bad luck bestowed upon someone out of jealousy, or by fate to restore balance. Unfortunately, nothing would be restored in this story. Kostas did manage to defend his thesis and receive his PhD, but passed away a year later. Martine and I attended the defense ceremony in Athens, and saying goodbye, knowing it was the last time we would see him, was incredibly difficult. We were young – it was utterly unfair.

More than twenty years later, this piece was written during a week when everything I undertook somehow worked out beyond expectations. Life was smiling at me once again, which shines through in the melody as well as in the upbeat 7/16 dance rhythm native to the Thrace region. It is known as mandıra in Turkish Thrace, mandilatos (μαντηλάτος) in Greek Thrace, and răčenica (ръченица) in Bulgarian Thrace. In all three languages, the name refers to the handkerchief that dancers hold (mendil, mandili, and răčenik, respectively).

With the piece’s title, I wanted to commemorate the events of ’99 and the fragility of life in general. The nazar (eye bead) is the ubiquitous Eastern Mediterranean protection against the evil eye and bad luck. My personal experiences with it are a bit underwhelming: I remember a nazar, a souvenir from Turkey, hanging from the rearview mirror of my first car, a Citroën 2CV, right after a crash it had failed to prevent. Or had it perhaps saved our lives?

Molars of Karydomys debruijni, a species named after palaeontologist Hans de Bruijn (1931–2021) belonging to the extinct Miocene hamster genus discovered by Kostas Theocharopoulos (1966–2001).

[7] Manastırka / Poustséno / Pušteno

First release: Európe (2019) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Modes: folkloristic forms of makams Hüseynî, Hicaz and Kürdî | Metre: 16/16 (2-2-2-3-2-2-3, poustséno/pušteno) | Musicians: Christos Barbas (kaval), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Nikos Papaioannou (cello), Taxiarchis Georgoulis (oud), Michiel van der Meulen (tambura), Pavlos Spyropoulos (double bass), Sergios Voulgaris (bendir)

This piece is inspired by a melody I once transcribed from memory, one that I think I learned from my father, who neither remembers who taught him, nor where the song is from, nor what it is called. Based on the type of melody and rhythm we agreed it must be Macedonian. It might very well be that the song as we used to play it does not actually exist: in criminological terms the chain of evidence is hopelessly compromised, and I must admit that I never found a melody sounding much like it. […] ‘Manastırka’ refers to a region [in Macedonia] where at least the metre must be somewhat familiar. For those who are unsatisfied with this etymology, the name could however also refer to Šljivovica Manastirka (Шљивовица Манастирка), an internationally famous Serbian brand of Slivovitz having 45% of a substance that has a great and proven potential to unite us all. [Full original track notes]