Pîrî Reis | Liner notes

Introduction

Pîrî Reis, my debut album, is the result of a hugely enjoyable, six-day hit-and-run mission to Crete, where five musicians I admire greatly recorded six of the modal compositions I have been writing over the last couple of years. To me, composition is a journey of exploration into the world of modal music, in which I specifically take inspiration from the beautiful makam music of İstanbul. Makam music drew from, and could perhaps be considered the pinnacle of, the many modal traditions that existed in the vast Ottoman empire. The title of this album combines these elements: Pîrî Reis (‘Captain Piri’, 1465?–1553) was a legendary Ottoman admiral and cartographer. His extraordinary maps, one of which was used for the album artwork, happen to not only relate to the exploration aspect of how I see composition, but also to my profession as a survey geologist.

The album is what came out after attending modal composition seminars at Labyrinth Musical Workshop for a couple of years. Delivering Pîrî Reis therefore felt a bit like a final exam, which is exactly how Crispijn Oomes described it in his review for MixedWorldMusic.com. The album basically just happened. It was lyra virtuoso and composer Kelly Thoma who first encouraged me to record some of my work, but while I did assemble a group and took it to the studio, I hadn’t put much thought in what to do with the results. By the time we finished recording, violinist Giorgos Papaioannou urged me to make a proper album and release it on CD, and as the recordings had turned out well I agreed. However, when I was asked what the album was going to be called, I realised I forgot a rather crucial detail. It was around 03:30 AM, I was dozing off in a chair in the studio control room, and sound engineer Vangelis Apostolou was wrapping up and needed to fill out the master metadata. “Give me five minutes”, I said. After a bit of thinking and googling on my telephone, Pîrî Reis popped up. This Ottoman admiral and cartographer is particularly famous for his 1513 world map, which he compiled from various sources and gives a good account of the extent of exploration of the New World at that time. Pîrî Reis was not an explorer himself. He did not discover the western Atlantic shores he charted. He did however find himself a Dutchman on an eastward musical journey and help him mark his first destination.

Michiel van der Meulen

Bunnik, March 2022

‘Plasgezicht met visser, een kerk aan de einder’ (View on a lake with fisherman, a church at the horizon) by Willem Weissenbruch (1864–1941). The scene is just about as Dutch as it gets, but I think watching such mixed skies and listening to the many colours in modal music are kindred experiences.

Track notes

[1] Şehnaz yürük semâî

Musicians: Harris Lambrakis (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Manolis Kanakakis (kanun), Yorgos Mavromanolakis (oud), Marijia Katsouna (tombak) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Şehnaz | Usul: yürük semâî (6/8, 3-3)

This piece was written overnight, in bed, in the small village of Agios Vasileios, where I spent a weeks to attend a modal composition seminar. Şehnaz is a beautiful compound makam with several in-built modulations that somehow remind me of a particular type of Dutch weather: windy, partially cloudy, with alternations of sunshine and rain. It is this type of weather that I’ll start missing when I am in the South and have clear blue skies for weeks in a row (…much to the amazement of the locals and my wife).

This opening piece was also the first composition that the group tried during the first reherasal session. I was a bit nervous, which is quite an unusual state for me to be in. I had somehow managed to get a group of accomplished musicians together to play my compositions, the products of a novice in contemporary modal music. I didn’t know Harris Lambrakis and Manolis Kanakakis personally at that time. I knew their music and reputation and considered them way above my leage. I wasn’t sure how the pieces would turn out, or whether the musicians liked the music at all. But after only a couple of seconds, just one or two bars into this piece, I knew. We were going to be fine.

[2] Kürdî saz semâî / Zaman Yolcusu

Musicians: Harris Lambrakis (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Manolis Kanakakis (kanun), Yorgos Mavromanolakis (oud), Marijia Katsouna (bendir) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Kürdî | Usul: aksak semâî (10/8, 3-2-2-3)

Tribute note – Wouter Swets (1930–2016) was a well-known and notable ethnomusicologist, musician, composer, teacher and writer. Through lectures, workshops, radio programs, scholarly articles, polemics, CD reviews, and performances with his ensembles Čalgija and Al-Farabi, Swets inspired countless music lovers and musicians to share his passion for the modal music traditions of the Balkans, Anatolia, Arabia and Central Asia, his understanding of which was rooted in the massive collection of beautiful melodies he collected over his life. Even though he would have argued that ‘world music’ does not actually exist as a genre, he has often been called its godfather in the Netherlands.

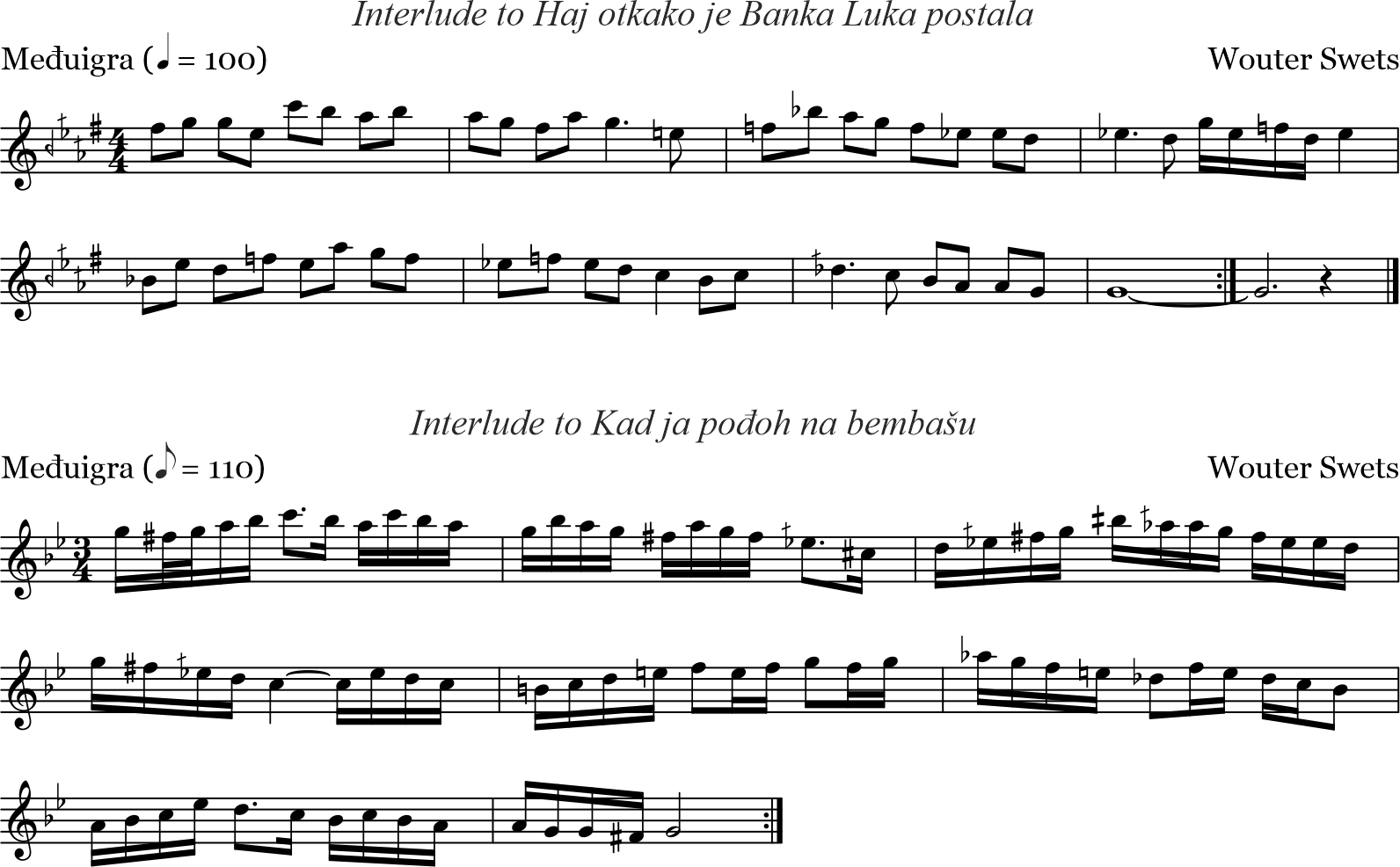

Swets was one of the more colourful and entertaining house guests I remember from my early youth, who would always make music when he stayed with us. Even though I was too young to join in at that time, Swets played a pivotal role in my musical upbringing, first of all through my father who was member of Čalgija in its first line-up. Later on, I played with more Čalgija veterans, all of whom were thoroughly infused with Swets’ views and practices, referring to the man at least once per rehearsal. So in my musical life, he never seemed far away. Swets passed away shortly after I thought of paying him a visit to present some of my modal compositions, and I ended up playing at his funeral instead. After the ceremony, I thought that it would be appropriate to dedicate a composition to him. I chose this saz semâî because the way its teslim modulates reminds me somewhat of the brilliant interludes Swets wrote to the Bosnian-Serbian folk songs ‘Haj otkako je Banka Luka postala’ and ‘Kad ja pođoh na bembašu’.

The semâî’s title ‘Zaman Yolcusu’ (time traveller), refers to the way he made arrangements, by which he brought traditional melodies back to what he thought must have been their pristine versions, guided by a combination of science and his impeccable sense of aesthetics. He would for example remove western-style harmonisation and its limitations to microtonality, or restore complex rhythmic patterns in order to resolve phrasing issues he attributed to unruly metric simplifications. Whether or not Swets would have actually liked this saz semâî, I cannot tell. His approval could never be taken for granted: as testified by his occassionally vehement reviews and comments he was very critical. His extraordinary analytical skills would have enabled him to spot any deficiency prima vista, and this piece is unorthodox in several ways. I am confident, though, that he would also be able to recognise and perhaps appreciate the respect it carries, for a man who influenced the lives of many fellow musicians, as well as for the music he loved and stood for.

Two interludes by Wouter Swets, reproduced, with permission, from his handwritten manuscripts; the Turkish Arel-Ezgi system was used instead of the original western equal-tempered notation. Copyright rests with the composer.

[3] Anamnisi

Musicians: Harris Lambrakis (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Manolis Kanakakis (kanun), Yorgos Mavromanolakis (oud), Marijia Katsouna (tombak) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Büselîk | Usul: curcuna (10/8, 3-2-2-3)

I worked on this piece on my way to Greece, during stopovers in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania and Epirus, finishing it at our final destination Zacharo while staying with friends. The title came to me on the ferry from Patras to Venice we took on our way back home, while passing the beautiful mountainous shores of Albania. The Greek word anamnisi (ανάμνηση) means memory. It is not a particularly original title for a piece of music, but rather than some trite reminiscence it refers to the effects of a severe brain hemorrhage that my father Albert had suffered earlier that year. The stroke cut short the final stages of his scientific career and eradicated my parents’ retirement plans. My father lost not only his memory and speech, about half of which he would later regain, but also the ability to play his accordion (read more about his music here). This frustrated him to the extent that he enjoyed listening to music less and less. This album was the first music he enjoyed without reservation.

[4] Dügâh saz semâî

Musicians: Harris Lambrakis (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Manolis Kanakakis (kanun), Yorgos Mavromanolakis (oud), Marijia Katsouna (bendir) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Dügâh | Usul: aksak semâî (10/8, 3-2-2-3)

This piece I wrote in 2013 during another modal composition seminar at Labyrinth Musical Workshop. This means that several people were composing in the same form and makam simultaneously, which is always interesting and brings out the endless possibilities that modal music offers. As usual, Ross Daly had explained the makam—Dügâh, a compound of Sabâ and Hicâz—after which the students would compose individually and try subsequent iterations of their pieces with the group. Peter Jacques, an American-born, Athens-based clarinetist, produced several versions of a Dügâh saz semâî, but Ross kept insisting that he should stay more in the lower register. A hint of frustration started to shine through Peter’s friendly west-coast demeanor: “Er, Ross, I don’t want to be a pain, but why do you keep telling me to stay low, while you allow Michiel to go up all the way to the eighth degree?” Ross replied, “well, yes, but Michiel comes back down straight away”, and left it at that. This small exchange was very typical of the way we were taught. Once the composing started it was the music that should be doing the talking.

One of the most memorable moments during the Pîrî Reis sessions was the recording of this piece’s giriş taksim (introductory improvisation). Oud player Yorgos Mavromanolakis was a bit nervous, but he was one of those musicians who is able to convert pressure into focus. He captured the essence of both Dügâh—a particularly dark, heavy makam—and this particular piece extraordinary well. He took his time, and somehow managed to project peace of mind and withheld tension at the same time, paving the way for the band which did exactly the same. I will never forget this moment. Sadly, Yorgos would pass away on 17 July 2017 at the age of only 39 years, just weeks before we would reunite to record my second album Europe.

[5] Nev-Eser peşrev / Muhabbet

Musicians: Harris Lambrakis (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Manolis Kanakakis (kanun), Yorgos Mavromanolakis (oud), Marijia Katsouna (bendir) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Nev-Eser | Usul: Devr-i kebîr (28/4, 6-4-4-6-4-4)

This piece represented somewhat of a challenge. I like makam Nev-Eser a lot as a built-in modulation of makam Nihâvend, but creating an entire composition in it was not easy. Tanbur player and educator Murat Aydemir wrote: “The makam Nev-eser can be considered an unproductive makam for which there are few compositions. It is difficult to create the expected feeling of conclusion when performing this makam” (Turkish Makam Guide, Istanbul: Pan Yayıncılık, 2010). I will not go in the details of how this relates to tonal structure, just think of the makam as chili pepper: delicious in a dish, but challenging as a main ingredient. When I finished it, I liked it but feared that is was maybe a bit too weird. However, when I first tried it with Ross Daly, he said that he wouldn’t change a thing. When I included it in the material for this album, I expected the musicians to maybe not like it, and considered it reserve material. However, it turned out to be Giorgos Papaioannou’s favourite piece, and when we were listening to its recording Yorgos Mavromanolakis said: “Michiel! You did it!”

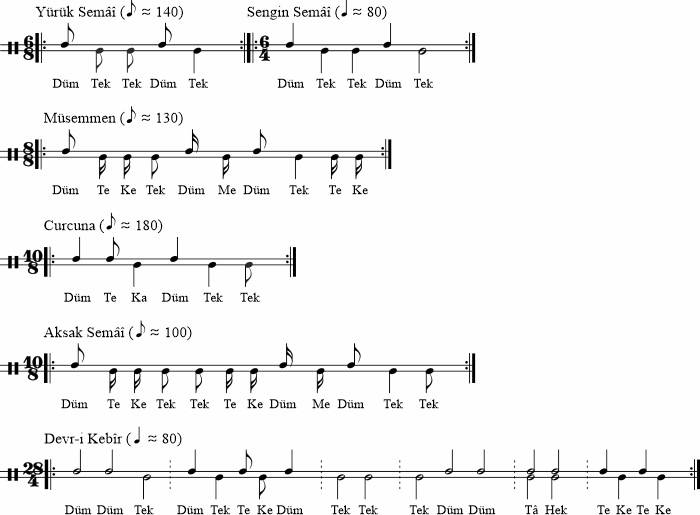

This is my first peşrev, one of the larger forms in Ottoman art music. Large refers particularly to the usul (rhythmic cycle) of choice: devr-i kebir. It may first seem to come across as a standard 4/4 metre, but when you’ll listen to the frame drum closely you hear that the cycle spans the individual lines of the piece. It took quite an effort for me to internalise this metre, the structure of which is shown in figure 2 below.

[6] Nihâvend saz semâî / To Laïko

Musicians: Harris Lambrakis (ney), Giorgos Papaioannou (violin), Manolis Kanakakis (kanun), Yorgos Mavromanolakis (oud), Marijia Katsouna (bendir) | Composition: Michiel van der Meulen | Makam: Nihâvend | Usul: aksak semâî (10/8, 3-2-2-3)

This saz semâî was one of the first full compositions I created outside a seminar, so without guidance. It felt a bit like riding a bicycle for the first time, wobly at first but more confident down the road. As a matter of fact, the first six notes of the teslim (refrain section) came to me while cycling to work. It is actually difficult to compose while cycling if the metre is impossible to align with a your average pedalling rhythm. So either, you ignore this (which I find difficult), you will inadvertedly cycle rather awkwardly (as I do), or you will only produce slow rock ballads in this way (which I don’t).

When I was rehearsing the piece on my own at Labyrinth Musical Workshop in Houdetsi, Ross Daly came in from an adjoining room and asked, “what piece is this?” When we then tried it together his somewhat enigmatic comment was, “this is a real, proper composition.” I was very happy.

The title ‘To Laïko’ refers to a mainstream Greek musical genre, characterised by lightness and westernness. I find this a light piece, especially towards the end, and makam Nihâvend, which resembles a harmonic minor scale, is arguably one of the most easily digestable and relatable Oriental modes to Western ears. The piece is also light in the sense that it contains some (possibly nerdy) humor. Starting out in usul aksak semâî (10/8), it changes to 8/8 (usul müsemmen; 03:27) and then to 6/8 (yürük semâî; 04:36). Progressing from 3-2-2-3 to 3-2-3 to 3-3, the piece basically behaves like a bellows that squeezes out two’s.

Explanatory notes

Makam

A makam is a mode in Turkish/Ottoman art music, but the term may also refer to the modal system as a whole. The number of individual makams is estimated at about 600. Some 120 are formally defined, that is, they have been categorized and are associated with repertoire. Only about 20 of these are widely used today. Each makam has a unique combination of its intervalic structure (cinsler) and melodic progression (seyir), unlike western scales, which are defined by their intervalic structure alone. The most concise description of a makam is obtained by envisaging it somewhere along a line that can be drawn between tonal material and a fully-fledged melody. There is no harmony in traditional makam music. Western-style second voices and chords are incompatible with the subtlety of a makam’s cinsler, and chord progression rules and aesthetics clash with its seyir. Hence, accompaniment will generally not go beyond a drone or the occasional bass note produced by the lower melody instruments. Musicians play the same melody, contributing with the specific sound and register of their instrument and the ornamentation possibilities it offers. Richness is achieved by heterophony.

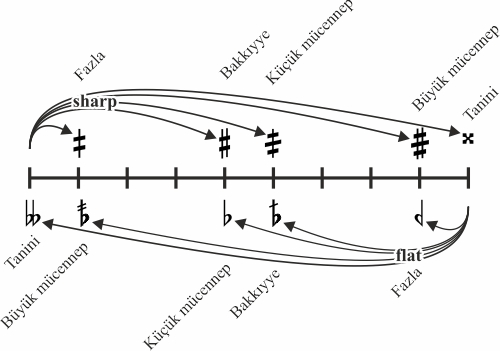

Notation

Makam intonation cannot be captured in standard western notation, which is based on twelve-tone equal-tempered tuning. Pîrî Reis’ scores use the Turkish Arel-Ezgi system, which divides a whole tone in 9 equal mircotonal intervals (koma’s). Accidentals are placed at the 1 (fazla), 4 (bakkıyye), 5 (küçük mücennep), 8 (büyük mücennep) and 9 (tanini) koma intervals (Figure 1). Even though this system is more sophisticated than western notation, it can still only approximate makam intonation, which is flexible, depending on melodic progression and tonal centre of gravity.

Figure 1. The Turkish Arel-Ezgi system divides a whole-tone interval in 9 komas.

Makams in Pîrî Reis

The primary makams used in Pîrî Reis are şehnaz, kürdî, dügah, nev-eser and nihâvend, but as the pieces modulate repeatedly, there are quite a few more makams to be heard. With the exception of Ανάμνηση, the title of each piece references the primary makam, along with its compositional form or, in the first piece, its usul, the rhythmic counterpart of makam (Figure 2). Just as makam is more than a scale, usul is more than a metre; it is a rhythmic cycle that underlies and structures the composition. Musical forms used include saz semâî (3) and peşrev (1). Differing in usul, both these forms have a structure consisting of four movements (hâne) each followed by a refrain (teslim). The usul of a saz semâî is aksak semâî (10/8), but it is customary to have a rhythmic change in the fourth hâne. Kürdi Saz Semâî changes to yürük semai (6/8, which is also used throughout the first composition in şehnaz), Dügah Saz Semâî to sengin semâî (6/4) and Nihâvend Saz Semâî first to müsemmen (8/8) and then to yürük semâî. Ανάμνηση uses curcuna thoughout (10/8), so with the same metre as aksak semâî but with a completely different rhythm and feel. Peşrevs use even metres, particularly the very long ones that allow composers to create phrases that are very long without losing their balance and direction. Nev-eser Peşrev uses devr-i kebir (28/4), the length of which is already impressive by western standards, but there are even longer usuls, up to 128/4.

Further reading

This brief outline of makam music mainly serves to introduce the notation system used in Pîrî Reis’ score book. The Turkish Music Makam Guide by Murat Aydemir is a recommended source for further information, which is provided in a very practical way, with scores and audio examples. A large makam sheet music collection can be found on www.neyzen.com.